‘The Voice that Breathed over Eden’ by John Keble (1792-1866)

The voice that breathed o’er Eden That earliest wedding-day, The primal marriage blessing, It hath not passed away. 4 Still in the pure espousal Of Christian man and maid The Holy Three are with us, The threefold grace is said. 8 For dower of blessed children, For love and faith’s sweet sake, For high mysterious union Which naught on earth may break. 12 Be present, Holy Father, To give away this bride, As Eve Thou gav’st to Adam Out of his piercėd side. 16 Be present Holy Jesus, To join their loving hands, As Thou didst bind two natures In Thine eternal bands. 20 Be present, Holy Spirit, To bless them as they kneel, As Thou for Christ the Bridegroom The heavenly spouse dost seal. 24 O spread Thy pure wings o’er them! Let no ill power find place, When on ward through life’s journey The hallowed path they trace. 28 To cast their crowns before Thee, In perfect sacrifice, Till to the home of gladness With Christ’s own bride they rise. 32

Considering the Poem

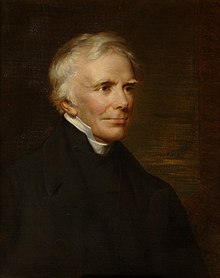

John Keble (1792-1866) was a Church of England priest and, with Pusey and Newman, originated the Oxford Movement that revived high church ideals. He was also Professor of Poetry at Oxford from 1831 to 1841 and a distinguished hymn writer. In this poem and hymn he shows a command of exactly the kind of formal skill and word craft that are required by the job of writing the text for an occasional hymn. The verse is clearly and simply structured in repeated four line stanzas with the same rhyme schemes (the second and fourth line rhyming each time, nearly always on a one-syllable word). This extreme clarity of organisation and style probably makes the words more easily set by a composer, presumably each stanza requiring an eight bar stretch of music.

Clarity, not the knotty subtleties of more introspective religious poetry, is what Keble must aim for in his wording as well as in the general structure of the hymn. The meaning, at least the surface meaning, needs to be, and here can be, grasped immediately by the singing congregation.

At the same time, and without making the work difficult or using anything but the plainest of English words, he imbues the verses with real depth of religious truth. The sacramental meaning of the marriage lives in almost every jot of the hymn: the ceremony is set in the whole of biblical Christian history from the ‘primal marriage’ in Eden (1-4) to the end of time and the rising to the ‘home of gladness’ (31), and the core verses (four to seven) interweave the physical actions of the wedding – the giving away (14), the joining of hands (18), the kneeling (22) – with the inner, spiritual meaning of the actions shown by the presence of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit in both the ceremonial actions themselves and in this hymn that describes them.