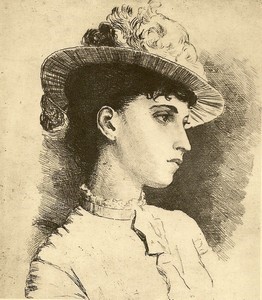

‘Christ in the Universe’ by Alice Meynell (1847-1922)

With this ambiguous earth His dealings have been told us. These abide: The signal to a maid, the human birth, The lesson and the young Man crucified. 4 But not a star of all The innumerable host of stars has heard How he administered this terrestrial ball. Our race have kept their Lord’s entrusted Word 8 No planet knows that this Our wayside planet, carrying land and wave, Love and life multiplied, and pain and bliss, Bears, as chief treasure, one forsaken grave. 12 Nor, in our little day, May his devices with the heavens be guessed, His pilgrimage to thread the Milky Way, Or his bestowals there be manifest. 16 But, in the eternities, Doubtless we shall compare together, hear A million alien Gospels, in what guise He trod the Pleiades, the Lyre, the Bear. 20 O be prepared, my soul! To read the inconceivable. To scan The million forms of God those stars unroll When, in our turn, we show to them a Man. 24

Considering the Poem

General speculation about whether there could be life on other planets goes back to at least the 17th century and the jolt people got from being informed by the astronomer Kepler that the sun, not we on earth, was the centre of the solar system. Suddenly, it was, maybe, not all about us. The Victorian polymath William Whewell had reinvigorated the debate about the possibility of life beyond earth in his essay On the Plurality of Worlds (1853). Whewell thought intelligent life unlikely but Meynell’s poem (probably written in 1895) pushes on with the subject, exploring, in particular, what the discovery of such life would mean for Christians.

She starts at home. The earth is ‘ambiguous’ (1) because it is both very little and very important. (God’s work has been done here; there is a ’forsaken grave’ (12).) She then imagines the universe and asks what apparently ‘alien Gospels’ (19) may there exist. The Victorians had astronomy, an alertness to tricky questions about science and religion, and, of course, new knowledge of other, alien cultures on earth acquired through their colonial activity. They made organised studies of the cultures they found (the Anthropological Institute was founded in 1871) and discussed the theological implications of their encounters with these foreign and non-Christian cultures. Difference was something the Victorians were used to finding in the world, but Meynell, rather daringly, puts the subject on a universal basis.

In the poem, as it is in the universe, she makes the earth as peripheral and as small as possible: it’s a ‘wayside planet’ (10); it’s just a ‘ball’ (7); the essential things that have happened on it can be said succinctly. (Thus, the whole of the Gospel from the annunciation to the crucifixion is condensed in a fifteen word summary (2-4).) She puts our world in its context of vast unknown space and then uses the dramatic contrast between the little earth and the endless universe to confront the reader with some perplexing ideas.

She presumes that no being in the ‘innumerable host of stars’ (6) has heard about God’s work on earth or about our keeping of his ‘Word’ (8), but tells us that, one day, when we hear the ‘million alien Gospels’ (19) believed by faraway beings, we will understand exactly how and in ‘what guise’ (19) the good news has been communicated in those unimaginable, and unimaginably distant, worlds. She thinks that the forms of expression of the good news will be different in different places but the truth contained inside those various forms will always and in all places be the same (17-23).

The final verse sets free the suppressed excitement that the speculative exploration of astral spaces has built up (21). In the final line, as a suitable climax to the poem’s exploratory thought-experiment, Meynell looks calmly forward to universal reconciliation and her tone of voice is one of happy fulfilment: we shall show a ‘Man’ (24) to those other worlds and they, in turn, will show to us their own identities of the one God.