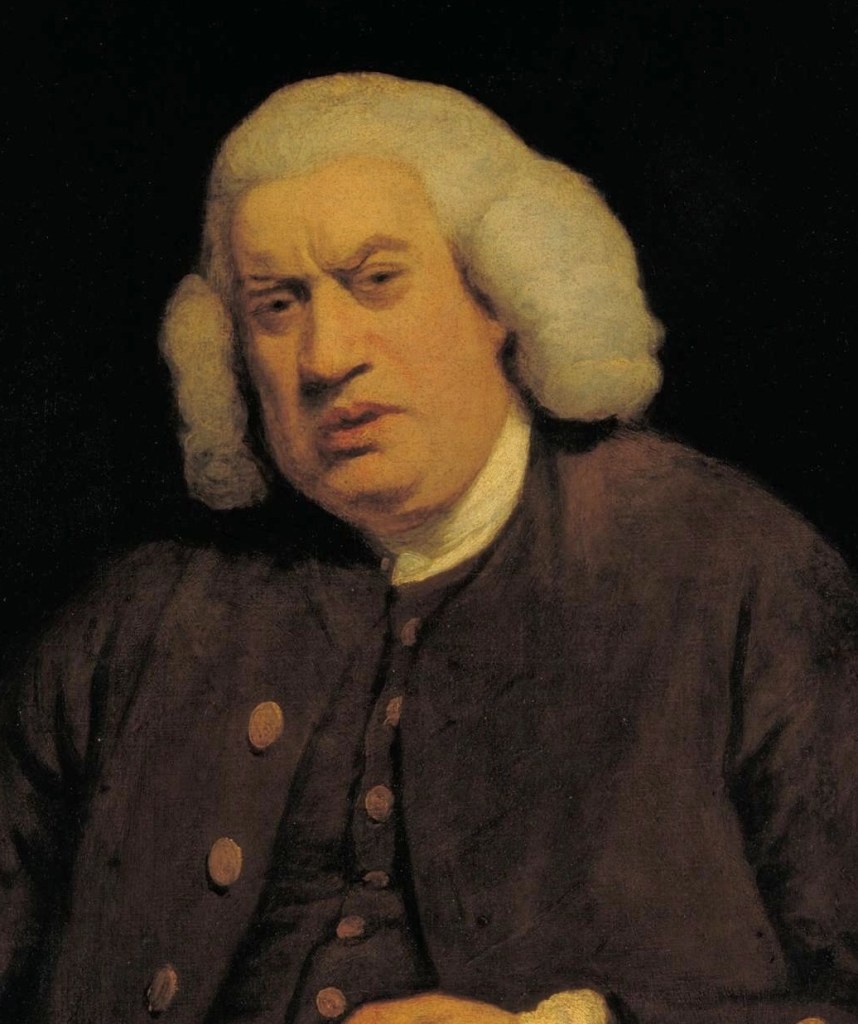

‘On the Death of Dr Robert Levet’ by Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)

Condemn’d to hope’s delusive mine, As on we toil from day to day, By sudden blasts, or slow decline, Our social comforts drop away. 4 Well tried through many a varying year, See Levet to the grave descend; Officious, innocent, sincere, Of ev’ry friendless name the friend. 8 Yet still he fills affection’s eye, Obscurely wise, and coarsely kind; Nor, letter’d arrogance, deny Thy praise to merit unrefin’d. 12 When fainting nature call’d for aid, And hov’ring death prepared the blow, His vig’rous remedy display’d The power of art without the show. 16 In misery’s darkest caverns known, His useful care was ever nigh, Where hopeless anguish pour’d his groan, And lonely want retir’d to die. 20 No summons mock’d by chill delay, No petty gain disdain’d by pride, The modest wants of ev’ry day The toil of ev’ry day supplied. 24 His virtues walk’d their narrow round, Nor made a pause, nor left a void; And sure th’ Eternal Master found, The single talent well employed. 28 The busy day, the peaceful night, Unfelt, uncounted, glided by; His frame was firm, his powers were bright, Tho’ now his eightieth year was nigh. 32 Then with no throbbing fiery pain, No cold gradations of decay, Death broke at once the vital chain, And free’d his soul the nearest way. 34

Considering the Poem

Dr Robert Levet was one of the collection of paupers, waifs and strays that shared Johnson’s house just off the Strand in Gough Square, London. In his famous dictionary of 1755, Dr Johnson defined the word ‘officious’ (7) as ‘kind, doing good offices’ – it hadn’t acquired the negative associations that the word has for us, and here it rather sums up Levet’s devotion to his daily duty, a devotion upon which all his other virtues were erected. He was a penniless and hard-working doctor who ministered, often with little or no pay, to those even poorer and more bereft than he was himself. Of course, his death was of no importance to anyone that did not know him. No-one was about to make a public statue of Dr Levet so, instead, Johnson’s calm elegy stands as a touching tribute to his obscure friend and, like the statues of the great, it stands firm and true, an orderly, balanced and lucid monument in words to a life well lived.

The monumental character of the poem seems created by every decision Johnson has made about how to commemorate his friend. The structure is regular: each verse is a sentence; each line is a two-part phrase that has a clear rising and falling cadence with a slight but perceptible pause half-way through each line; his virtues are collected as we read through the poem, verse by verse, as Johnson records Levet’s painstaking care for the sick poor. Even while Levet himself was weakening into old age, the power of his ‘art’ (16) offered help to his patients whose meagre payments created just enough money for the doctor to enable him to work again for them on the following day (23-24).

The enumeration of Dr Levet’s Christian virtues holds this monumental obituary together. So does the slightly strange spatial imagery. We start with an image of Levet’s work as an underground activity, carried out in a hope that can never be satisfied (1-2); in verse two we see him ‘descend’ (6) further; then further still we descend as he visits the suffering in ‘misery’s darkest caverns’ (17) until his own death leniently releases him, his ‘free’d’ soul flying to God the nearest or quickest way (34)

.

There are thousands of things Johnson could have told us about his friend but he concentrates on the doctor’s general virtues as they were expressed, not in talk about airy schemes to make perfected humans for fantastic utopias, but in a life of diligent, hard and practical work; it is Dr Levet’s daily efforts that, by the end of the poem, make him, for us and the poet, not just an obscure, penniless and suffering doctor but an all-time model for a lay Christian life. We are left, like Johnson himself, believing that the ‘Eternal Master’ must have judged Dr Levet’s ‘single talent’ to have, indeed, been ‘well employed’.