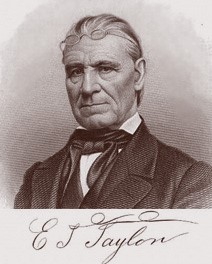

‘38 Meditation. 1 John 2:1 – An Advocate with the Father’ by Edward Taylor (1645- 1729)

Oh! What a thing is Man? Lord, Who am I? That Thou shouldst give him Law (Oh! golden line) To regulate his Thoughts, Words, Life thereby. And judge him Wilt thereby too in thy time. A Court of Justice thou in heaven holdst To try his Case while he’s here housed on mould. 6 How do thy Angells lay before thine eye My Deeds both White and Black I daily doe? How doth thy Court Thou Panelist there them try? But flesh complains. What right for this? let’s know. For right, or wrong I can’t appeare unto’t. And shall a sentence Pass on such a suite? 12 Soft; blemish not this golden Bench, or place. Here is no Bribe, nor Colorings to hide. Nor Pettifogger to befog the Case, But Justice hath her Glory here well tri’de. Her spotless Law all spotted Cases tends. Without Respect or Disrespect them ends. 18 God’s Judge himselfe: and Christ Atturny is, The Holy Ghost Registerer is found. Angells the sergeants are, all Creatures kiss The book, and doe as Evidences abound. All Cases pass according to pure Law And in the sentence is no Fret, nor flaw. 24 What sayst, my soul? Here all thy Deeds are tri’de. Is Christ thy Advocate to plead thy Cause? Art thou His Client? Such shall never slide. He never lost His Case: He pleads such Laws As Carry do the same, nor doth refuse The Vilest sinner’s Case that doth him Choose. 30 This is His Honor, not Dishonor: nay No Habeas-Corpus against His Clients came. For all their Fines His Purse doth make down pay. He Non-Suites Satan’s Suit or Casts the Same. He’ll plead thy Case, and not accept a Fee. He’ll plead Sub Forma Pauperis for thee. 36 My Case is bad. Lord, be my Advocate. My sin is red: I’m under Gods Arrest. Thou hast the Hint of Pleading: plead my State. Although it’s bad thy Plea will make it best. If Thou wilt plead my Case before the King: I’le Wagon Loads of Love and Glory bring. 42

Considering the Poem

You are bound to wonder whether, when Edward Taylor was writing the first six words of this Christian meditation in verse, he was thinking of the question ‘What a piece of work is a man?’ in Hamlet’s soliloquy in the second act of the famous play. It’s a well-known and big question, after all. Shakespeare and Taylor, however, go in opposite directions in the search for an answer: Shakespeare’s character goes towards the general and the abstract, as is his bent, but Taylor, the Massachusetts puritan poet, typically goes towards a particular and individual source for an answer – himself. Hamlet ends up with a conclusion about human beings in general: ‘Man delights me not’ but Taylor ends up with a grim, personal and confessional conclusion: ‘My case is bad’ (37).

Perhaps this introspective direction is the place to which his puritan sensibility, with its emphasis on the believer’s relationship with God, was bound to lead him in his effort to understand where he himself stood with his maker, how he would be judged when the day came and whether he had grounds for hope.

The poem is about God’s judgement. It depends on a single, sustained metaphor: the comparison between the process of earthly law and judgement, on the one side, and the process of divine law and judgement on the other side of the comparison. Taylor is sometimes called a ‘metaphysical’ poet like Donne, Crashaw and other 17th century poets; but Taylor, while sometimes difficult, is not really anything much like them in style. His writing may be difficult but it’s rarely tortuous or self-consciously clever. Here, for example, he is completely obvious and overt about the comparison between the two processes of law. We don’t have to untie any difficult twists in the comparison ourselves because he takes us through the points of contrast one by one in the first five verses.

Through God’s grace-filled attitude to our unworthy selves, as it is expressed to us in scripture, we and Taylor know the ‘Law’ (2) we must follow and we know that, our ‘Thoughts, Words, Life’ (3) will be judged in a heavenly court even as we lie mouldering in our grave (6). This basic, existential position is established in the first stanza. From then on, the contrasts are drawn out as we move through the poem. The roles in the process of heavenly jurisdiction are neatly imagined as perfected examples of roles in an earthly court: the angels (7) watch over us and so can give evidence for or against us, God is the ‘Judge himselfe’ (19); Christ will act as the solicitor’s role as ‘Atturny’ (19) as is explained in the reference to 1 John that is included in the poem’s title; the Holy Spirit is the court recorder of ‘Regesterer’ (20), and the angels can act as organisers of the oath-making process (21-22) as well as laying out the evidence. Though perverse, unruly humans may complain, the structure of heavenly judgement is, of course, sound.

In this it is unlike the judgement of human courts. It may be that we complain (10) and fuss but thee divine court ‘tends’ (or, manages) all cases without fear or favour and in complete impartiality (17-18); moreover, there is no blemish in the heavenly court, no bribery, and, ultimately no error or fretting disagreement because heaven’s law is pure and perfectly applied.

Then, at the fifth stanza, the direction of the poem alters. The author turns away from the general constitution of the divine court and considers his own case and his own fate. The question-and-answer style that has dominated the writing in the early verses carries on into this verse as Taylor poses rhetorical questions about Christ’s role in the court’s judgement. He serves the laws not a particular defendant and cannot automatically be an advocate for Taylor’s suit or plea but he has complete mercy for those who show repentance by turning to him, by choosing him, even though the individual may be the ‘Vilest’ sinner (30). The poet hopes that his faith puts him in this right place. Christ, Taylor asserts in the sixth stanza, will do anything to save a repentant sinner: he will ensure that the law of Habeas Corpus applies (that the sinner is not condemned indefinitely to bodily imprisonment without trial); he will excuse the poor of having to pay fees and costs by the practice of ‘Sub Forma Pauperis’ (36), the special arrangements for the poor. So, there is hope.

With the baleful, almost laconic tone of the first four words, the final stanza begins the final movement of the poem. It is Taylor’s profoundly felt plea for mercy from a merciful judge. He knows his sin is ‘red’ and his ‘case’ is bad and that only mercy can turn that bad to good. At this point, the poem has completed the movement from general truths about justice to a critical, defining moment in a particular, personal life. His salvation depends on the pleading of his case by Christ and will, because his faith is matched with Christ’s merciful plea on Taylor’s behalf, ‘Waggon Loads of Love and Glory bring’ (42).

This final colloquial phrase reminds us that he is comfortable using a very wide range of vocabulary from the colloquial to the formal (in this case the specialised vocabulary, or register, of trials and courts). You can find other examples of colloquial speech elsewhere in the poem: ‘pettifogger’ (15), perhaps in the exasperated ‘Oh’ that jerks the poem into life and in the lapel-grabbing questions that pepper the earlier verses; these conversational features wrestle throughout with the abstruse and specialised terminology of the law.

Taylor’s choices in the areas of tone, vocabulary and manner show he believes that the language suitable for use in poetry extends to the very edges, both formal and informal, of the language itself. In this, as in his subject matter and the personal relationship he establishes with the reader, he is one of the sources of the confessional style of writing that runs through the history of writing and into our present time.