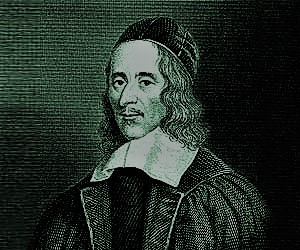

‘Easter Wings’ by George Herbert (1593-1633)

Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store,

Though foolishly he lost the same,

Decaying more and more,

Till he became

Most poore: 5

With thee

O let me rise

As larks, harmoniously,

And sing this day thy victories:

Then shall the fall further the flight in me. 10

My tender age in sorrow did beginne;

And still with sicknesses and shame

Thou didst so punish sinne,

That I became

Most thinne. 15

With thee

Let me combine

And feel this day thy victorie:

For, if I imp my wing on thine,

Affliction shall advance the flight in me. 20

Considering the Poem

Although it is usually printed in the form used here, George Herbert (1598-1633) really meant this poem to be printed at a ninety degree angle, on its side, as it were, for reasons that become obvious once you realise that the central figurative idea in the poem is that of a bird’s wings in flight (8). The wings represent the rising of the human soul that is made possible by the redemptive resurrection of Christ. In the first verse, the bird is the lark; in the second verse, it’s a hawk. Perhaps Herbert thought it was important to make a reader turn the book around to read the poem because that engagement does at least something to emphasize the fact that sharing in the saving grace that Easter brings requires a person’s decision and action.

Each verse has the same form exactly and also enacts the same emotional process. The first half of each verse has a dwindling, sinking movement culminating in a bare, bleak, terse statement of our fallen condition: ‘Most poore’ [5], and ‘Most thinne’ [15]. In the second verse, though, Herbert intensifies the tone, making it more personal and more urgent by changing from a general focus on mankind as a whole (‘he became’ [4]) to a laser-like focus on himself, the speaker in the poem (‘I became’ [15]).

At the centre of each verse are the repeated words ‘With thee’. From that half-way point in each verse, a new movement – an ascending movement – begins. We, and George Herbert, are carried upwards, away from the slough of original sin, by finding power in Christ’s redemptive love and the spiritual energy it offers.

A rising flight is brought visually and aurally to our minds by the exhilarating image of the lark’s singing climb and then, in the second part of the second verse, by the speaker’s combining [17] with the ascending Christ, upon whose wing, the speaker can ‘imp’ [19] himself, the unusual word ‘imp’ referring to the act of repairing a damaged feather in the wing of a trained hawk by the attaching of another feather. The crucified Christ in this image is the damaged hawk who provides the motive power for the rising of the intrinsically helpless and incomplete man that is ‘imped’, or grafted, onto him.

Then, in the final line, as in the line that ends the first verse, Herbert, sweeping back through time, draws together the Fall and the atonement for that Fall in a terse, paradoxical and surprising assertion – an arresting climax to this Easter poem.