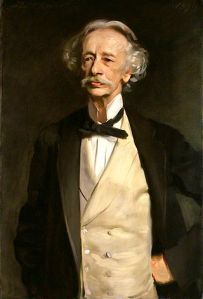

‘The Toys’ by Coventry Patmore (1823-1896)

My little son, who looked from thoughtful eyes And moved and spoke in quiet grown-up wise, Having my law the seventh time disobeyed, I struck him, and dismissed With hard words and unkissed, 5 His mother, who was patient, being dead. Then, fearing lest his grief should hinder sleep, I visited his bed, But found him slumbering deep. With darkened eyelids, and lashes yet 10 From his late sobbing wet. And I, with moan, Kissing away his tears, left others of my own; For, on a table drawn beside his head, He had put, within his reach, 15 A box of counters and a red-veined stone, A piece of glass abraded by the beach And six or seven shells, A bottle with bluebells And two French copper coins, ranged there with careful art To comfort his sad heart. 21 So when that night I prayed To God, I wept, and said: Ah, when at last we lie with tranced breathe, Not vexing Thee in death, And thou rememberest of what toys 25 We made our joys, How weakly understood, Thy great commanded good, Then, fatherly not less Than I whom Thou hast moulded from the clay 30 Thou’lt leave Thy wrath and say, ‘I will be sorry for their childishness.’

Considering the Poem

This Victorian domestic poem tells a story using two time scales, long and short. The short timescale is in three episodes: in the first episode (1-5), Patmore tells us how he came to hit his “little son”; in the second (6-21), he returns to the son’s room in shamed contrition; the last of the day’s three episodes (22-23) moves forward another step in time to later “that night” and to Patmore’s evening prayer. The prayerful speech to God imagines his own death, and takes us beyond the concrete, immediate and human world into an ultimate and infinite reality.

Because the poem begins in a quiet, confessional tone, the speaker’s sudden violence (4) and then the stuttering release of information about the death of his wife (6), is shocking. The mother’s death (in fact, Patmore did lose his first wife) is the earliest event mentioned in the poem so can be seen as the starting point for the poem’s longer time scale running from her death to Patmore’s imagined death-dialogue with God, perhaps many years after the single evening in which the short, main action of the poem takes place.

We can use the events in the longer time scale to explain the events of the evening. The dead mother is alive and active in the distressed life of both the father and the son: although the wrathful father’s impulse is to dismiss the pleadings of the patient, angelic wife, visiting him in thought (4-6), it is the awareness of her kindness, we infer, that softens his wrath, and causes him to return to the boy’s room (7).

Patmore, alone and observant. describes the signs of the boy’s solitary grief and his own rediscovered tenderness (9-13). Unusually, the climax of the poem’s action is a list – in fact, a heart-breaking catalogue of the little toys and treasures that the boy has assembled to console himself. At this point, as we leave the scene of his innocent suffering, we are closest to the working of the child’s mind, to his interior life, to his misery.

The poem is penitential. The final lines of prayer (23-32) arise exactly and completely from the evening’s experience, and explain its significance in the context of eternity.

The contrite father (now in the same position to God as his son was to him) pleads to the Father for the mercy, love and pity which, in his anger, he himself had not originally shown either to his deceased wife or, indeed, to his own, helpless little son.