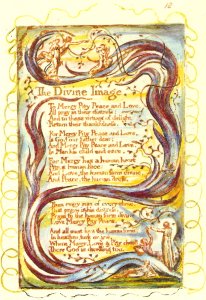

‘The Divine Image’ by William Blake (1757-1827)

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love All pray in their distress; And to these virtues of delight Return their thankfulness. For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love Is God, our father dear, And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love Is Man, his child and care. For Mercy has a human heart, Pity a human face, And Love, the human form divine, And Peace, the human dress. Then every man, of every clime, That prays in his distress, Prays to the human form divine, Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace. And all must love the human form, In heathen, turk or jew; Where Mercy, Love & Pity dwell There God is dwelling too.

Considering the Poem

The divine image in the poem is the human being, the tangible, embodied human being, created in the image of the Maker.

The poem comes from William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience (1789). As you’d think, the book comprises two contrasting sets of poems, one of which takes a confident, celebratory view of us all, as a type of being, and the other which explores and presents the darker, pessimistic dimension of human life and human beings.

Often, a single poem in the innocence set will have a contrasting, companion piece in the Songs of Experience. In the Songs of Experience, the poem called The Human Abstract investigates the operation of evil in human life and another of Blake’s poems from this time (not finally included in the Songs of Experience) begins ‘Cruelty has a Human Heart/And Jealousy a Human Face …’.

But here we are reading Blake’s most positive view of the human being.

His approach, as in all the pieces in the Songs of Innocence, is based on achieving an effect of complete clarity, openness and simplicity of expression. The vocabulary is simple enough, there’s a lot of repetition of critical words, and nothing interrupts the mood of fresh, disingenuous happiness. Even the form is calming: the poem is a short lyric in the balled form (four line stanzas with eight then six syllables in the pairs of lines) but with a lot of half rhymes perhaps to inhibit the chug, chug, chugging-along feel of the usual narrative balled. The plainest thing about it, though, is probably the guileless, calmly explanatory tone of voice – a bit like the tone of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress which Blake would have known.

It’s quite an achievement to use simple language to communicate complex, even unsettling and problematic ideas. (Though it’s rather the other way round in some of his later prophetic books, in these poems, Blake achieves just that.) The ruling idea in the whole lyric is the idea of embodiment. Well, perhaps that’s not such a complicated idea if one is looking at it as a Christian. We know about the way that humans are made in God’s image, and we know that virtues like pity, mercy, peace and love are not just abstract qualities that float about in the air or in our minds but have to be, if they are to exist in an understandable way and as a representation of the divine that we down here can perceive in our world’s space, time and matter, embodied. That’s what Blake is telling us when he says mercy has a human heart: not of course that mercy originates in us but that when it, or pity, love or peace, are embodied in us, we are being what we were supposed to be.