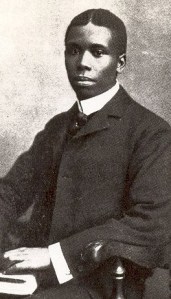

‘When Malindy Sings’ by Paul Lawrence Dunbar (1872-1906)

G’way an’ quit dat noise, Miss Lucy— Put dat music book away; What’s de use to keep on tryin’? Ef you practise twell you’re gray, You cain’t sta’t no notes a-flyin’ Lak de ones dat rants and rings F’om de kitchen to de big woods When Malindy sings. 8 You ain’t got de nachel o’gans Fu’ to make de soun’ come right, You ain’t got de tu’ns an’ twistin’s Fu’ to make it sweet an’ light. Tell you one thing now, Miss Lucy, An’ I’m tellin’ you fu’ true, When hit comes to raal right singin’, ‘T ain’t no easy thing to do. 16 Easy ‘nough fu’ folks to hollah, Lookin’ at de lines an’ dots, When dey ain’t no one kin sence it, An’ de chune comes in, in spots; But fu’ real malojous music, Dat jes’ strikes yo’ hea’t and clings, Jes’ you stan’ an’ listen wif me When Malindy sings. 24 Ain't you nevah hyeahd Malindy? Blessed soul, tek up de cross! Look hyeah, ain't you jokin', honey? Well, you don't know whut you los'. Y' ought to hyeah dat gal a-wa'blin', Robins, la'ks, an' all dem things, Heish dey moufs an' hides dey face. When Malindy sings. 32 Fiddlin’ man jes’ stop his fiddlin’, Lay his fiddle on de she’f; Mockin’-bird quit tryin’ to whistle, ‘Cause he jes’ so shamed hisse’f. Folks a-playin’ on de banjo Draps dey fingahs on de strings— Bless yo’ soul—fu’gits to move ‘em, When Malindy sings. 40 She jes’ spreads huh mouf and hollahs, “Come to Jesus,” twell you hyeah Sinnahs’ tremblin’ steps and voices, Timid-lak a-drawin’ neah; Den she tu’ns to “Rock of Ages,” Simply to de cross she clings, An’ you fin’ yo’ teahs a-drappin’ When Malindy sings. 48 Who dat says dat humble praises Wif de Master nevah counts? Heish yo’ mouf, I hyeah dat music, Ez hit rises up an’ mounts— Floatin’ by de hills an’ valleys, Way above dis buryin’ sod, Ez hit makes its way in glory To de very gates of God! 56 Oh, hit’s sweetah dan de music Of an edicated band; An’ hit’s dearah dan de battle’s Song o’ triumph in de lan’. It seems holier dan evenin’ When de solemn chu’ch bell rings, Ez I sit an’ ca’mly listen While Malindy sings. 64 Towsah, stop dat ba’kin’, hyeah me! Mandy, mek dat chile keep still; Don’t you hyeah de echoes callin’ F’om de valley to de hill? Let me listen, I can hyeah it, Th’oo de bresh of angel’s wings, Sof’ an’ sweet, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” Ez Malindy sings.

The Poem Considered

It’s usually easier to see what’s in a poem than to see what’s missing that might normally be there. Here, the author gives us no descriptive information about any of the five named characters (four humans, including Mandy the nurse, and a dog) except the sound they make. Perhaps this is one cause of the fact that, by the end of the poem, Malindy begins to float away from physical life and become a kind of disembodied, wraith-like spiritual presence. Dunbar tells us no more than he has to about the people in the poem and leaves plenty of opportunity for us to use hints in the text to infer the details of the situation for ourselves, and enjoy ourselves in the effort of sense-making. (What reading poetry is all about, maybe?)

The voice, or speaker, in Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s poem addresses a speechless interlocutor called Lucy, who (because he is nearby and within view) knows him, or her. In fact, a better word than speaker or voice in the case of this poem might be thinker or observer because, at least until the last verse, he or she says nothing aloud. The text of the poem comprises the thoughts and feelings of the observer: it is an interior monologue, a stream of consciousness, for the most part. This is why we need to make our own decisions, as readers, about the relationships in the poem, of course. It would be completely unnatural in a realistic stream of unspoken thought to explain details about person, place and identity. When we are reflecting, or talking to ourselves, we just don’t do that because we are not addressing anyone – at least anyone that doesn’t already know those details.

Dunbar is meticulous in adhering to the rules of the inner monologue. He also, consequently, has to give considerable thought to the problem of how, given that he isn’t an omniscient author outside the events of the poem and is using one of the characters inside the narrative of the poem as a voice, he can make sure that we are given enough information – and just the right kind of information – to able to infer details of place and person for ourselves. He has mastery of this extremely difficult technique: he has to show us, not tell us the details.

As regards place, by the end of the first verse, we know that probably we are in a plantation house on a large estate and we infer that Lucy is a young daughter of the plantation owner’s family. She is well-resourced with costly items: a piano (probably), sheet music and so on. Lucy does not reply to what is quite a barrage of mocking criticisms and questions because they are not spoken aloud. We can tell that Lucy also knows, to some extent, Malindy, the subject of the poem – though not well enough, probably, to have really listened to her sing (25). At the poem’s start, the observer seems to be near Lucy, perhaps in a hallway outside the room in which she is practising music. He’s near enough, anyway, to notice that she is using written sheet music as she practises. Malindy is not present and seems to be outside the house working in ‘de kitchen in the big woods’ (7).

So, what we are reading is actually an internal monologue, the thoughts of a house servant with some standing and freedom of movement inside and outside the building. Lucy certainly would reply, wouldn’t she, if she heard the words abruptly addressed to her in the first verse, not to mention the collection of unfavourable comparisons between her and Malindy that make up the rest of the poem? (The fact that the speaker’s words are thoughts that cannot be spoken tells us something about his inferior social status in relation to Lucy, of course.)

The poem is not set in a tightly defined historical moment. Dunbar may be thinking back to antebellum southern life in the USA, or he may be setting his poem in a later period, during his own life, and after emancipation had been decreed (if not achieved). If so, he would be writing about the relationship between masters and workers rather than masters and slaves. But the slightly fuzzy timing makes little difference: his fundamental subject is the relationship between a white, European-orientated culture and an African-American culture.

Dunbar often writes in standard English but here – and this is certainly the most noticeable stylistic feature of the poem – he uses dialect, the natural language of the poem’s speaker. The author had a choice between this and Standard English and went for the authenticity and truth of dialect. The language style matches the observer and voice of the poem. Apart from getting the benefits of characterization and verbal energy that dialect always brings, he also, without the fuss and bother of clunky, explicit explanation, conveys a strong sense of a rift, a passive stand-off, really, between two cultures and their languages – the culture of the estate owner’s family expressed in Lucy and the culture of the owned slaves.

We miss the point of Dunbar’s poetic aims, however, if we think that dialect writing indicates casualness about the craft skills of versification. Here, as always, Dunbar shows that he is a fully-fledged and proud poetic craftsman who is able to use the traditional forms of English poetry, exactly and correctly. The crafted, traditional versification is not for show: it contains and manages the bustle of action, sound and thought that makes up the poem’s subject matter.

The poem is written in octets: eight line stanzas each comprising two four line quatrains, each quatrain having a rhyme scheme in which the second and fourth lines rhyme and the final line (abcb/defe), usually, takes the form of a refrain in a shorter line. Dunbar uses a pattern of paired stressed then unstressed syllables as a rhythmic unit running generally through the whole poem. This metrical unit (trochaic is the literary term) doesn’t work as easily in English as the more common iambic unit (that is, an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable).

So, why does Dunbar take this trouble? The basic reason is that he wants to fit the verse rhythms to the observer’s voice which, given that he is always on the front foot and challenging, is best heard with a strong stress at the start of each line. Dunbar uses an upfront rhythm for an upfront voice and, again, shows what he can do as a craftsman. So, the dialect vocabulary reflects one culture, an African-American one, and the verse-craft another culture, the art conventions of the European poetic tradition. Dunbar marries them in his work just as Malindy sings both a traditional European hymn tune, ‘Rock of Ages, and a spiritual, ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’.

The emphasis in the poem – the thing that makes it dramatic – is the underlying contrast (or opposition) between the two cultures. The contrast is built in the poem around the differences between Lucy’s music and the music made by Malindy: Lucy’s music is in a ‘music book’ rather than in her (2); it is preserved for reproduction in ‘lines and dots’ (18); it is ‘educated’, art music (58). Malindy’s music, on the other hand, is free, expressive, natural and spontaneous; it is neither politely confined in the drawing room, nor safely detained in the music room. Malindy’s music belongs to the ‘big woods’ (7). The poem explores these qualities of her deeply-felt music and its effects on listeners, on other musicians, even on the woodland birds.

Most importantly, her music is connected to spiritual insight and to God. The speaker develops this idea in the final three verses. He begins to speak and not just to think: he orders Towsar the dog to stop barking; he tells Mandy the nurse to quieten the child in her care. They obey. He listens, and so do we, to Malindy whose humble praises rise up to ‘the very gates of God’ (56) and seem, to the speaker, as he recalls listening to them in the evening, ‘holier’ (61) even than the church bells. The poem ends in a moment of quiet transcendence as the speaker, alone and outside the plantation house, hears the echoes of Malindy’s song as the breath of ‘angels’ wings’. Malindy, from the start ephemeral, is now transformed into a Christian spirit, busy making order and beauty in the world.

t