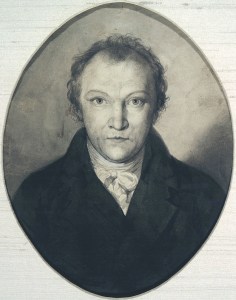

‘The Clod and the Pebble’ by William Blake (1757-1827)

“Love seeketh not itself to please, Nor for itself has any care, But for another gives its ease, And builds a Heaven in Hell’s despair.” 4 So sung a little Clod of Clay Trodden with the cattle’s feet, But a Pebble of the brook Warbled out these metres meet: 8 “Love seeketh only self to please, To bind another to its delight, Joys in another’s loss of ease, And builds a Hell in Heaven's despite.” 12

Considering the Poem

What could be simpler? A brief, highly focused poem made from the imagined utterances of two completely different objects, a clod of earth in a field of cattle and a pebble in a flowing brook. The governing idea here is, of course, to make an antithesis between the sentiments of the Clod and the Pebble.

The antithesis, though, is not just in the words and ideas of the Clod and the Pebble but is baked in to the form of the poem itself. William Blake does this by repeating the form of the first verse in the third verse, and then using the first two lines of the middle verse to name the Clod of Clay and give its location and the second two lines of the middle verse to name and locate the second speaker, the Pebble.

From the point of view of its general organisation, the most important word in the poem is ‘But’ (7). It is the hinge in the middle of the two paralleled sections and begins the homeward journey in the poem. This parallelism, or repetition of form – a phrase, a line, a verse, or whatever – gives the poem a design that pleases the eye (a virtue often undervalued in poetry) and a definitive, authoritative character.

The usual way of thinking about the poem is to treat the Clod’s giving, humble, selflessness as the Christian ideal of love. These qualities show up not only in the Clod of Clay’s speech but also in the description of it in the second verse which draws attention to its malleable, self-sacrificing nature: it gives, and alters its shape in response to the pressure of the cattle’s feet. In contrast, the Pebble is hard, and takes no shape from the running stream around it but, instead, forever asserts its individuality, shaping the flow of the water that passes it by.

Sometimes an antithesis like the one that this poem depends upon can be taken to imply some kind of balance between the two contrasting parts of the opposition, as if each were on one side of a level weighing-scale. It doesn’t, however, work to make an equation between the Clod and the Pebble here. The Pebble is a malevolent, selfish threat. Blake tells us that its will and hardness ‘builds a Hell’. This damning comment is amplified by the description of the chirpy complacency with which the Pebble sings out its philosophy. Perhaps anything hard would do the job, but an associative thinker like Blake instinctively uses a stone to stand for a view of life, surely recalling that stones in the bible are instruments of death, sterility, punishment and martyrdom.

One of the paradoxes of Christianity is the hope that the self-giving love and humility of the Clod of Clay triumphs and endures when the hardness of the Pebble fails. St Paul says in his Second Letter to the Corinthians, “When I am weak, then I am strong” (12: 9-10).

Blake’s moral poem dramatizes Paul’s words.