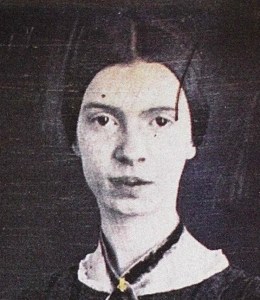

‘The Snake’ by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

A narrow fellow in the grass Occasionally rides; You may have met him, - did you not, His notice sudden is. The grass divides as with a comb, 5 A spotted shaft is seen; And then it closes at your feet And opens further on. He likes a boggy acre, A floor too cool for corn. 10 Yet when a child, and barefoot, I more than once at morn, Have passed, I thought, a whip-lash Unbraiding in the sun, - When, stooping to secure it, 15 It wrinkled, and was gone. Several of nature's people I know, and they know me; I feel for them a transport Of cordiality; 20 But never met this fellow, Attended or alone, Without a tighter breathing, And zero at the bone

Considering the Poem

Christianity is full of symbols. Many of these are animals and plants pulled aside from their life in nature to be given a special role in Christian discourse and writing: the vine, the seed, the fish, the dove, the lamb and, of course, the serpent, which was punished by God for beguiling Adam and Eve and told that ‘upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life’ (Genesis 3:14). Emily Dickinson was a Christian in her bones and, while this poem never mentions anything explicit about the religion, it is both a spiritual and a specifically Christian piece of work: it dramatizes her response to the snake and, in the end, makes a profound point about us and our problematic relationship with nature.

In her customary, apparently (but only apparently) artless way, Emily Dickinson disguises the formal planning in the poem with an informal, colloquial manner. The poem is, actually, in three distinct, eight-line episodes, each doing a slightly different job but with the overall aim of concentrating our attention on the sensory excitement of encountering the creature so that we too can understand, and know through feeling, the rapt fascination that she experienced in her encounters with the snake, the serpent of Genesis, the ‘narrow fellow’ of the poem’s opening line.

The snake shares nothing with us in his ‘narrow’, elusive body yet, while he belongs to an entirely different world and is detected only suddenly, or by silent signs of his movement in the parted grass (6-8), he is also a ‘fellow’ creature. The poem as a whole grows from the seed of the words ‘narrow fellow’ and, particularly, the idea of otherness and sameness, of both the creature’s difference from, and identity with, us.

The first eight lines are a general statement about the creature and the way we encounter it. The snake is glimpsed, partially and momentarily, as in a moment of sudden insight, an epiphany (13-16). The second section of the poem (9-16) dramatizes in colour, pattern, movement (but not in sound) the poet’s personal, childhood experience of the fascinating but alien snake. The instinctive and cultural fear of the creature, with its associations of sin and evil, is amplified in the final section of the poem (17-24) until we reach a climax of reactive emotion as Emily Dickinson’s breathe tightens and she is emptied by something she calls ‘zero at the bone’ (24), a terror at the distance in being between herself and the snake.

She also recalls her ‘cordiality’ (20) for several of ‘nature’s people’ – another phrase, like ‘narrow fellow’, that expresses both our identification with other creatures (‘people’) and yet our difference (‘nature’s’) from them. So, while the final four words of the poem blazon out Emily Dickinson’s instinctive terror at the sight of the snake, taking the poem as a whole, we can see that she presents both her sense of fellowship with (1), and her fear of, the reptile (24). In doing this, she is reminding us of one of our most complicated existential problems: we both belong, and do not belong, to the natural world of which we are almost a part, but not quite.