‘This Endris Night’ Anonymous (15th century)

This endris night I saw a sight, A star as bright as day, And ever among, a maiden sung, ‘Lullay, by, by, lullay.’ This lovely lady sat and sung, And to her child did say, “My son, my brother, father, dear, Why liest thou thus in hay? 8 My sweetest bird, thus ‘tis required, Though thou be king veray, But nevertheless I will not cease To sing ‘by, by, lullay’.” The child then spake in his talking, And to his mother said, “Yea, I am known as heaven-king In crib though I be laid. 16 For angels bright down on me light; Thou knowest 'tis no nay: And for that sight thou may’st delight To sing, ‘by, by, lullay’." "Now, sweet son, since thou art a king, Why art thou laid in stall? Why dost not order thy bedding In some great kinge's hall? 24 Methinks 'tis right that king or knight Should lie in good array: And then among, it were no wrong To sing 'by, by, lullay'." ‘Mary mother, I am thy Child, Though I be laid in stall; For lords and dukes shall worship me, And so shall kinges all. 32 Ye shall well see that kinges three Shall come the twelfth day. For this behest give me thy breast And sing, by, by, lullay.’ ‘Now tell, sweet son, I thee do pray, Thou art my love and dear — How should I keep thee to thy pay, And make thee glad of cheer? 40 For all thy will I would fulfil — Thou knowest well, in fay; And for all this I will thee kiss, And sing, by, by, lullay.’ ‘My dear mother, when time it be, Take thou me up on loft, And set me then upon thy knee, And handle me full soft. 48 And in thy arm thou hold me warm, And keep me night and day, And if I weep, and may not sleep, Then sing, by, by, lullay.’ ‘Now sweet son, since it is come so, That all is at thy will, I pray thee grant to me a boon, If it be right and skill - 56 That child or man, who will or can Be merry on my day, To bliss them bring - and I shall sing, Lullay, by, by, lullay.’

NOTES: (a) ‘This Endris Night’ = This Past Night; (b) ‘ever among’ (3) = every now and again; (c) ‘veray’ (10) = absolute or true; (d) ‘no nay’ (17) = not deniable; (e) ‘to thy pay’ (39) = suitably; (f) ‘skill’ (56) = correct.

Considering the Poem

The old word, ‘Endris’, in the title of this 15th century ballad, meant ‘recent’ or ‘just past’. There are inevitably a few other obsolete or changed words in a poem that’s about six hundred years old, but there’s nothing here that can do more than momentarily impede our understanding of this movingly human account of maternal love, the nature of which appears not to have changed a jot over the years.

A 15th century reader would probably be hearing rather than reading this verse. One of the reasons for the evolution of the ballad form was that, because of its predictable pattern of rhymes and rhythms, it was easy both to learn for a reciter and to follow for a listener. Like images in the church, the ballad (or hymn, as this one became) could be used to convey information about the gospel to a popular audience that most worshippers could not read. Just as we do, the medieval listener would expect the ballad to tell them a story. Although a story is told here – a section of the nativity story, of course – almost no time passes during the ballad and the narrative, such as it is, relies entirely on dialogue rather than a sequence of actions.

Dialogue can sweep backwards and forwards in time and, particularly, can express a speaker’s passing feelings directly. The story here is one about the internal lives of mother and child. This balance in favour of dialogue and internality, and away from plain narration, give the ballad an unusual lyrical quality. We have, then, a ballad with a degree of delicacy and feeling that we rarely find in this form of verse.

Mary and the child Jesus speak alternately in pairs of verses, each pair ending with the graceful, lullaby refrain that crystallises the lyrical gentility of the poem’s tone. Mary understands the divinity of her child and worries that he rests in a mean bed of hay. He is all things and in all relationships (7); he is a ‘king’ (10). Surely, he should be in a ‘kinges hall’ (24) wearing ‘good array’ (26). What she does not yet understand, the child Jesus explains to her: he affirms that he is ‘heaven-king’ (15) and reminds his mother that his riches are divine ones, received from the brightness brought down to him by angels (17). He reminds Mary (and the hearer or reader) of his superiority to worldly kings by predicting the future, obeisant visit of the three kings (33-34) described in Matthew’s account of the nativity.

Mary’s yearning to do the right thing for the child, to make him happy, to show her love for him in endearments and in her delicacy of feeling, runs through each of her dialogues and the mutuality of this love is expressed in the reciprocating speeches of the child.

The verse itself, not just the feelings it refers to, has a role to play here, too. It embodies her yearning in its tone and in its endearments but it also has a lyrical music in it, especially in the lullaby refrain, of course, but there are also other lyrical effects: a lot of internal rhyming (‘this’ and ‘kiss’ [43], for example); frequent alliteration and the sound-echoing within lines as consonant and vowel sounds repeat in nearby words. Also, the extreme simplicity of the vocabulary – mainly words of one syllable and none of more than two – give a lucidity to the verse that directs our response to the plain truth of the speakers’ feelings.

The mood darkens only in the dialogue exchanges that comprise the last four verses. When the Jesus child says, ominously, ‘when time it be’ (43), to what is he referring? It can’t be his birth. That has already occurred. What he referring to, surely, is his death?

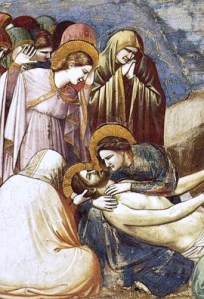

In the 14th century, two ancient genres, or types, of painting had become particularly celebrated in northern Europe: the Lamentations of Christ and, developing out of that genre, the Pieta. The first depicted the group receiving the dead body of the crucified Christ; the second, the Pieta, depicted just the grieving mother Mary and Jesus, typically showing her holding up (‘on loft’ [44 ]) the body of her dead son in an attempt to engage with him as she had done when he was a child.

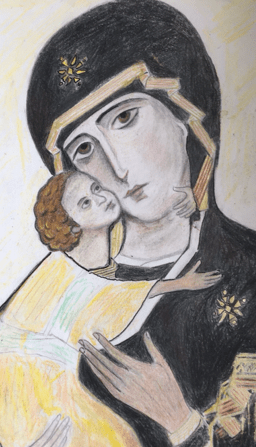

The art works (like the one above, a detail from by Giotto’s ‘Lamentations of Christ’) show Mary experiencing the pain she had been shown foresuffering as she looks with a mixture of love and sorrow at Jesus, as if knowing his fate, in so many Madonna and Child paintings and icons.

We know, as does her son, that she will faithfully carry out the requests that child Jesus has made in his final speech (42-50) so the lyrical ballad we have just read can end with a reminder to the faithful that each year in the calendar of Christian churches, there is a day set aside to remember Mary’s love and suffering, the two states of mind, here, as sometimes in life, almost inseparable, one from the other.