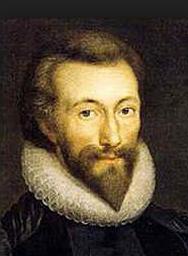

‘Holy Sonnet 13′ by John Donne (1571-1631)

What if this present were the worlds last night?

Mark in my heart, O Soul, where thou dost dwell,

The picture of Christ crucified, and tell

Whether that countenance can thee affright, 4

Tears in his eyes quench the amazing light,

Blood fills his frowns, which from his pierc'd head fell.

And can that tongue adjudge thee unto hell,

Which pray'd forgiveness for his foes fierce spite? 8

No, no; but as in my idolatry

I said to all my profane mistresses,

Beauty, of pity, foulness only is

A sign of rigour: so I say to thee,

To wicked spirits are horrid shapes assign'd,

This beauteous form assures a piteous mind.

Considering the Poem

Like a surgeon who’s left a surgical instrument inside a patient or like a mechanic who’s left a spanner in the works, Donne has left something very uncertain inside this poem that we don’t discover straight away but which, in the end, guides us to its meaning.

Not that there’s anything fuzzy or uncertain in Donne’s mind about the fundamental material from which a human is made. Donne assumes that we, and he, have a body (9-12), a soul (2), a seat of personality, or heart (2) and a reasoning mind. In the poem, Donne’s reasoning mind is the voice addressing itself to his listening soul. That’s the dramatic situation that lasts through the whole poem: a speaker and a listener in a brief episode of anxious introspection that has been set in motion by the opening question which asks what it would mean if the end of days had come and the final judgement was imminent. That this will happen one day is a Christian belief that Donne shares with his 17th century readers.

In fact, the shocking opening question begins a kind of thought-experiment and shows us, firstly, that what Donne is frightened about is actually not dying itself but the judgement that will follow death and, particularly, the fear that he will be found wanting so, in the first quatrain (1-4) of the sonnet, the soul is asked to state its position, saying exactly how it’s situated and whether the picture of ‘Christ crucified’ fills it with fear of an imminent judgement.

The crucified Christ is made real and certain to us through the sensory imagery deployed in the second quatrain (5-8). We are made to see, to be almost able to touch, the warm blood running in rivulets in the creases of Christ’s frowning forehead, to feel the weight of the bowed and pierced head from which the blood drops, to sense the liquid volume of the tears in Christ’s eyes – the compassionate tears shed for all human beings, even his persecutors, for whom, as the saviour, he dies. The fiercely physical imagery includes the poem’s second question: does Donne’s soul think Christ’s tongue (7) can pass a sentence of eternal death on Donne himself?

At this point, the poet helps us to perceive a difficult, underlying paradox: what fear should there be if the judgement we face is administered by an all-forgiving Christ who died in payment for human sin?

Here, in Donne’s company, we have passed into a realm of uncertainty. The answer to this question about the fate of the poet’s soul is not obvious, and is about to become less obvious still. We know, of course, because even the poem itself has reminded us, and Donne repeats the confidence emphatically in the exclamation, ‘No, no’ (9), that Christ forgives all, but the poem is about to leave a problem inside itself that slips into our minds a suspicion that Donne (and, by implication, us) may not, in fact, merit forgiveness.

The last quatrain (9-12) introduces this suspicion by means of an odd turn of thought that could easily be ignored, or treated just as a remnant of the traditional use of the sonnet form for love poetry. Actually, it is the heart of the uncertainty in the poem. Donne suddenly reminds us and his listening soul of his sexual adventures and the ‘idolatry’ with which he has worshipped his ‘profane’ (10) mistresses. He has flattered them into believing that their ‘beauty’ must have arisen from their inner ‘pity’ (11) and that they cannot be full of ‘rigour’ (by which he means a cold, rigid and unforgiving turn of mind) because they are not unpleasant in appearance (12).

But we are left, at this point in the poem’s unfolding, with a nagging uncertainty. Ideas about idolatry and profanity (11-12) are damningly serious words in a Christian poem and do, surely, give Donne a reason to be uncertain about the result of Christ’s act of judgement.

We are perhaps reassured, as is Donne, by the resounding confidence and certainty of the final line of the poem: the ‘beauteous form’ of Christ ‘assures a piteous mind’ (14). Donne is confident because he knows he can trust Christ’s qualities, if not his own fallible nature. As in the earlier account of the mistresses (11-12), and using the old notion that a person’s body is a sign of their mind, the ‘beauteous form’ of the crucified Christ can only indicate a pitying, forgiving mind. So, perhaps we end the thought-experiment with a confidence that all will be well with the individual soul, perhaps even with the souls of the profane mistresses and of the idolatrous Donne. The poem ends up by reminding us that our salvation depends in the end on God’s grace not on our own work or achievement.

But isn’t there something left in the poem’s body and organisation that leaves us just a little unsure, and perhaps concerned to right ourselves if there is some righting or repentance to be done before the last day, hypothetically close in the poem, does actually arrive?

Selected Poems: Donne (Penguin Classics): Amazon.co.uk: Donne, John, Bell, Ilona: 9780140424409: Books £7.85 (or £2.99 Kindle)