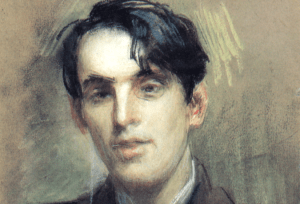

‘The Ballad of Father Gilligan’ by W B Yeats (1865-1939)

The old priest Peter Gilligan Was weary night and day; For half his flock were in their beds, Or under green sods lay. 4 Once, while he nodded on a chair, At the moth-hour of eve, Another poor man sent for hum, And he began to grieve. 8 ‘I have no rest, nor joy, nor peace, For people die and die’; And after cried he, ‘God forgive! My body spake, not I!’ 12 He knelt, and leaning on the chair He prayed and fell asleep; And the moth-hour went from the fields, And stars began to peep. 16 They slowly into millions grew, And leaves shook in the wind; And God covered the world with shade, And whispered to mankind. 20 Upon the time of sparrow-chirp When the moths came once more, The old priest Peter Gilligan Stood upright on the floor. 24 ‘Mavrone, mavrone!* The man has died While I slept on the chair’; He roused his horse out of its sleep, And rode with little care. 28 He rode now as he never rode, By rocky lane and fen; The sick man’s wife opened the door: ‘Father! You come again!’ 32 ‘And is the poor man dead?’ he cried. He died an hour ago.’ The old priest Peter Gilligan In grief swayed to and fro. 36 When you were gone, he turned and died As merry as a bird.’ The old priest Peter Gilligan He knelt him at that word. 40 ‘He who hath made the night of stars For souls who tire and bleed, Sent one of his great angels down To help me in my need. 44 He who is wrapped in purple robes, With planets in his care, Had pity on the least of things Asleep upon a chair.’ 48

NOTE: ‘mavrone’ (25) = alas

Considering the Poem

Yeats was interested in Irish nationalism and Celtic folklore all his life so the ballad form, a part, as it is, of popular culture, would perhaps have appealed to him for this reason. Here, he produces a literary version of the popular ballad with the Christian message that God’s grace is at work in the world. The old, tired priest, Father Gilligan, falls asleep rather than performing his duty of visiting a sick old man. By an act of grace, however, the dormant priest is replaced at the dying man’s house by a ministering angel.

Literary works in prose as well as poetry are very often a mixture of three modes, or kinds, of writing: narration (incorporating dialogue, usually), description and reflection. It is often useful, when we are in the first minutes of looking at a poem, to judge the relative weight of each of these three modes in the text we are reading: In a lyrical poem, it will often be reflection of some kind – a process of imaginative thinking making itself into a poem; perhaps all poems contain some degree of description of external things like a landscape or internal things like a state of mind; a ballad, however, needs above all to tell a story well by making a sequence of actions clear, keeping the pace moving along briskly and using dialogue as part of the narrative. Here Yeats follows exactly all the conventions of the ballad form to tell a story efficiently and effectively.

The conventional ballad is a predictable and traditional verse form that a poet can learn, practise and use. So, what are these conventions?

One of them you see can see clearly and immediately even without reading a word. A ballad is made from repeating four-line verses. When you look more clearly, you can see how each verse follows a pattern within itself. Firstly, each verse has a first and third line of, usually, eight syllables (or, that is, four iambic units) and, secondly, a shorter second and fourth line with six syllables (or three iambic units, or ‘feet’ as scholars call them). There are usually four strong stresses in the first and third lines and, as you might expect, three in the second and fourth line of each verse. It’s easy to see how this works when you read the poem aloud, perhaps slightly emphasizing the very regular beat of the strongly stressed syllables. (You’d be doing the right thing by reading it aloud because, as the name, ‘ballad’, suggests, the form is designed for performance.)

We then might also spot before reading in detail that there are two ways of pairing lines together in this verse form: the first and second lines of the verse go together, and so do the third and fourth because they represent a repeating pattern described above (four stresses then the next line three stresses). This pairing is emphasised in another way, too, because at the end of the second line (and nearly all the other second lines in the ballad verses), there is a pause marked with punctuation and with the pause comes a sense of the completion of a small but significant step forward in the story.

The other way of pairing the lines is to pair the second and fourth lines. As in our example above, the final word of the fourth line in each verse rhymes with the last word of the second line of each verse. This introduces a sense of completion stronger than just the minor pause after the second line. Each verse here is a sentence long. No more and no less. The full stop at the end of each verse rounds off a section of action and we sense that, in the next verse following, we’ll be moving on to a new section in the story.

These regularities are greater in Yeats’ ballad than in many older, popular ballads. But the strictly compliant versification is effective. It helps us to follow the story by delivering it in short steps, each a short module of meaning. The ballad works like a well-running vehicle that can carry the reader at a good pace through the events of the story, verse by verse. We don’t get waylaid by any unexpected changes in the writing itself. It is predictable enough for us to concentrate on just enjoying the tale.

Yeats is making conscious use of this old folk form. It’s almost as if he’s writing a demonstration piece to prove he can make a ballad following all the conventions and that he is a craftsman poet. His conscious understanding of the elements of form and style in the conventional ballad makes the poem a particularly useful one for us too, allowing us to see how a ballad works and how, in this case, the form can offer an easy, brightly-told story about the meaning of grace.

KINDLE EDITION £2.99 (at time of writing)

PAPERBACK EDITION £7.99 (at time of writing)