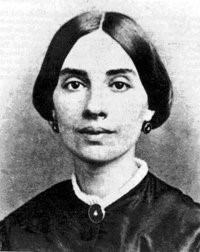

‘Because I could not stop for Death’ by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

Because I could not stop for Death,

He kindly stopped for me;

The carriage held but just ourselves

And Immortality. 4

We slowly drove, he knew no haste,

And I had put away

My labor, and my leisure too,

For his civility. 8

We passed the school where children played,

Their lessons scarcely done;

We passed the fields of gazing grain,

We passed the setting sun. 12

We paused before a house that seemed

A swelling of the ground;

The roof was scarcely visible,

The cornice but a mound. 16

Since then 'tis centuries; but each

Feels shorter than the day

I first surmised the horses' heads

Were toward eternity. 20

Considering the Poem

The point of all lyric poetry is to represent in words a mental episode of thought and feeling. Or, perhaps, there’s a better word than represent – maybe ‘enact’ – because what an intensely personal poet like Emily Dickinson wants us to do is to read the episode at the same pace and in the same sequence as it occurred in her mind. When it works, this amounts to a kind of magic.

This magic can be achieved through planning, writing, revision and other, sometimes painful, processes involved in writing. But Emily Dickinson disguises the hard work: the poem does read as if it were a faithful record of a particular train of thought and as if she were writing, instinctively and naturally, letting the poem grow into its form as she thought it.

Like many poems, it’s given coherence and integrity by being made from a set of binary oppositions: freedom of action is opposed to confinement; movement is opposed to stillness; urgency is opposed to repose; busy desire is opposed to detachment; life is opposed to death. When you look at the poem in terms of these oppositions, you can see that they appear, alter their position, change their associations, dissolve and re-form as we read.

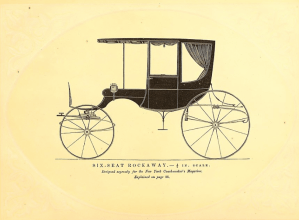

At the start, the speaker ‘could not stop for Death’. She is preoccupied with the urgent business of life, pursuing her desires, driven by her will to live and far too busy to stop still to consider death. In the final verse, she tells us that she is speaking from a point of time ‘centuries’ after her death (17) and that, from that point in time, the centuries that have passed seem shorter than the day she died; she is suspended in a pool of time, in a kind of eternal present, without will, desire or movement. Death, personified as a kindly, courteous gentleman, had, in effect, abducted her in the middle of her busy life and enclosed her in a carriage; there were no other passengers except the personification of ‘Immortality’ (4) so when we learn, in the final words of the poem, that Death’s carriage was pointed to ‘eternity’, we realise that a fulfilment has been reached as she and we have travelled together on the imagined journey that’s the poem. She has been made still and confined inside a vehicle that, whatever her will, travels with irrevocable purpose.

In the restricting confinement of the carriage, the passenger can do nothing so she lapses into quiet, observant stillness, setting aside ‘labor’ and ‘leisure’ (7) as the journey takes her through emblems and images of life, movement and vitality: the children playing, the crops growing, the sun setting, all processes in time. Her companions, Death and Immortality, remain solicitous. She does not resist.

The carriage’s confinement, at the climax of the poem in the fourth verse, gives way to an image of another, narrower confinement. The carriage pauses (13) before a strange ‘house’ (13). Up until that point, she had passed by (9, 11, 12, 13), not paused. Time hangs for a moment. She notices a ‘swelling of the ground’ (14) and a ‘cornice’ – a common architectural feature of a 19th century Christian grave. This place may be her resting place at journey’s end.

But she only pauses a moment and passes by to eternal life where there is no business or desire, only a state of still timelessness that seems to have no duration. Her kindly travelling companions, Death and Immortality, have done their work.

NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS:

(1) The carriage is a ‘Rockaway’ carriage that was popular with the 19th American middle classes so may well be the kind of vehicle that Emily Dickinson had in mind while writing; (2) The 19th century grave cornice shows a death’s head symbol with wings illustrating the flight of a soul to heaven, thus perfectly representing the meaning of the poem which realises a passage through physical death to eternal life.

Further Reading

The Selected Poems of Emily Dickinson (Wordsworth |Poetry Library)