‘My Cathedral’ by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882)

Like two cathedral towers these stately pines Uplift their fretted summits tipped with cones; The arch beneath them is not built with stones, Not Art but Nature traced these lovely lines, And carved this graceful arabesque of vines; No organ but the wind here sighs and moans, No sepulchre conceals a martyr's bones. No marble bishop on his tomb reclines. Enter! the pavement, carpeted with leaves, Gives back a softened echo to thy tread! Listen! the choir is singing; all the birds, In leafy galleries beneath the eaves, Are singing! listen, ere the sound be fled, And learn there may be worship without words.

Considering the Poem

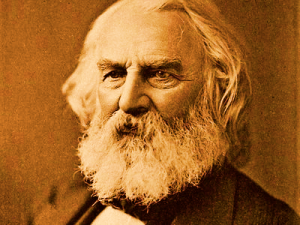

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was feted and famous in the 19th century and one of the last poets in America or England to be genuinely part of popular culture.

He was known for his own craft skill as a poet, of course, but also as one of the so-called ‘fireside poets’ whose work, like the bible, was read aloud in family settings, in parlour or cabin, for entertainment and edification and which doubtless kept many isolated families in communication of a sort with the wider society in which they lived. His long narrative poems, like ‘The Song of Hiawatha’ (1855) and ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’ (1860), were particularly suited to this type of transmission.

This poem is obviously not one of those lengthy story poems. It is a lyric in largely conventional sonnet form that expresses Longfellow’s particular views about Christian spirituality: it is organised, in the fashion of the so-called Italian sonnet, in two parts: a first of eight lines (the octet) and a second part of six lines (the sestet). The usual convention is to have a change of argument at the turn around point between the two parts; sometimes this can be done (as we’ve seen elsewhere in these articles) with the use of a simple conjunction to start the octet – perhaps ‘but’, or similar. Longfellow obeys this convention but his ‘turn’, as the moments are called, changes the tone and the relationship with the reader rather than the argument, which remains single and steady from start to finish.

The octet establishes that argument with complete clarity and the sestet continues it, though altering the situation by addressing us directly with a set of button-holing imperatives (‘Enter’, ‘Listen’, ‘listen’). Put as simply as possible, Longfellow argues that Christian worship works just as well in a wild, natural setting like the one he describes as it does in a church building.

Repetition ensures that this argument is clear. If you count the number of words in the poem for elements of church architecture, building and furniture, you’ll easily get to about a dozen: what Longfellow is doing by transferring these words into his descriptions of the natural scene is to transfer holiness from inside to outside churches, from the human-made environment to the God-made environment. In this he is following his Romantic predecessors who often wrote about finding God in nature so the poem is fairly conventional and therefore comforting in both form and content.

This is a positive thing, of course. Longfellow understands his audience and the the way his work is enjoyed; as a craftsman poet, he writes with all that in mind.

There are very few of us who haven’t at some point, even if only for a moment, been awe-struck by a natural sight, especially one with the grandeur Longfellow finds here in the north American pines. We might, too, have been impressed for a second or two by the numinous quality of a natural scene. Longfellow presents that intuitive moment as an insight into the divine world of the spirit. He identifies nature with God. Some of his contemporaries, like the English poet, Tennyson, were questioning this element of the Romantic view of nature and struggling to reconcile the cruelty and damage that is self-evidently part of the natural world with God’s goodness.

But an awed experience of the grandeur of nature is a timeless and meaningful pathway to an intuitive experience of the invisible world of the spirit.

We must thank Longfellow for his clear, strong communication of this truth.

KINDLE EDITION £1.49 (at time of writing)

PAPERBACK EDITION £6.35 (at time of writing)