‘Sonnet 146′ by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Poor soul, the centre of my sinful earth,

Feeding these rebel powers that thee array,

Why dost thou pine within and suffer dearth,

Painting thy outward walls so costly gay? 4

Why so large cost, having so short a lease,

Dost thou upon thy fading mansion spend?

Shall worms, inheritors of this excess,

Eat up thy charge? Is this thy body's end? 8

Then soul, live thou upon thy servant's loss,

And let that pine to aggravate thy store;

Buy terms divine in selling hours of dross,

Within be fed, without be rich no more. 12

So shalt thou feed on Death, that feeds on men,

And, Death once dead, there's no more dying then.

NOTES: (i) The spelling (and some inflexions) in the quotation from the Geneva Bible (1560) at the end of the consideration have been modernized; (ii) ‘upon’ (9|) = on, beyond; (iii) without (12) = on the outside.

Considering the Poem

While Shakespeare’s dramatic writing is dense with biblical echoes, allusions and, indeed, Christian moral assumptions, this sonnet is generally (and correctly) taken to be his only explicitly Christian poem. For this reason, it is bound to be interesting.

The sonnet is usually, of course, used as a form for the expression of romantic love. Here, Shakespeare uses it to investigate the spiritual damage caused by self-love which, because it draws attention away from the inner health of the soul and towards personal shows of transitory worldly status and appearance, can, in the end, only fail. Our souls are immortal. Our bodies are temporary.

As we might expect from a playwright, the poem is built on a dramatic situation. The sonnet is in the English (or Shakespearean) form comprising three quatrains and a final summative couplet. Shakespeare establishes the basic parameters of the dramatic situation in the opening line of the first quatrain. Because the theme is a universal one, it’s probably best to understand the speaking voice in the sonnet as an Everyman figure. He is having a lively conversation – or argument – with his soul. The disagreement between the two is about the soul’s behaviour: it is the central element in the speaker’s nature but he accuses it of spending its energies on external and superficial matters, on adorning the ‘outward walls’ (4), the appearance and general social persona of the speaker.

There is an element of self-satire in the situation, too. Blaming his soul for what are the man’s worldly weaknesses and vanity, although typically human – our personal shortcomings must always be someone else’s fault, of course – characterises the speaker as silly, weak and, especially in the opening two words of the sonnet, condescending. But we know that it is the man, not the soul, that has arrayed (or decked out ostentatiously) the ‘rebel powers’ of his body (2).

In the second quatrain, the questions continue to tumble out of this irritated, jumpy and querulous speaker: three more are added to the one in the first quatrain. The underlying images – common ones in Shakespeare’s sonnets – are to do with finance, property and legal arrangements. These images and their associated vocabulary are continued into the final quatrain (9-12) but, here, the little matrix of images is established in the question in lines 5 and 6: why, says the speaker to his soul, since you have only a short lease on your ‘mansion’, or body, do you waste time and money trying so hard to make it seem impressive to others? The speaker has cared and committed much expense, or ‘charge’ (8) on his person but it, and the expense, will be wasted. Worms will have it.

Shakespeare’s sonnets are tightly managed and dense (sometimes even rather compacted) pieces of writing. He often structures them as an argument, and this is what he does here. Logic words like ‘so’, ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ or, as here, the word ‘Then’ that starts the third quatrain (9), typically mark the stages and steps of the argument. We have reached a passage of the poem in which conclusions will be stated.

The speaker, having reflected, now understands more and is more confident in tone and manner. He gives directions to his soul. Until this point, the relationship between his soul and his material life have been topsy-turvey: the body and worldly concerns have taken precedence over spiritual matters. Now, the soul is told to make preparations to live on when the soul’s ‘servant’, the body, comes to its end (9).

The ‘store’ (10) referred to is the worthless material and worldly ‘dross’ (11) that the man has spent so long collecting, preserving and presenting as worthwhile to others. Let all these material things pine and let the store of dross be aggravated and weakened. After all, this part of the speaker is what should pine if his values were correct – not the soul that was said, at the start of the poem, to ‘pine’ (3). Let the body assume its right position as the servant of the soul and let the worldly part of the person pine and grow weak. After all, the ‘short lease’ possessed by the body is to be replaced, the speaker hopes, with ‘terms divine’ (11) in a new lease, an immortal contract.

It’s interesting that, although the sonnet is certainly in the English form, it does bear a shadow of the Italian form. The Italian form for the sonnet is based on an octet (or, eight line opening section) followed by a sestet (or, concluding six line section). Looking back at the poem’s structure, we can see that the questions end at the eighth line, at the point at which the speaker seems to have learned the lesson arising from his reflection, and, from the ninth line onwards, he is sure of the instructions he must give to his soul, sure of his own will and no longer the nervous, irritable voice of the poem’s start. A mental drama has been enacted in the poem and its form is caught in the shadowy Italian framework that co-exists with the English sonnet structure.

The role of the couplet in the English form is to provide a summative statement that emerges naturally from, and is at one with, the processes of both reasoning and emotion that have led up to it. Very often the couplet uses the core concepts of the poem (here, death and living) in a paradoxical, sometimes tortuous, concluding statement. The terminating couplet, as we might expect, is introduced with one of the logic words: So’ (13). Returning to, and completing, the food and feeding image that opened the sonnet (2), the speaker instructs the soul to ‘feed’, or be nourished on, its true, living awareness of ‘death’ (12-13). Death eats us all. But our awareness of its true meaning makes it possible for us to overcome and kill it (14): ‘there’s no more dying then’ (14).

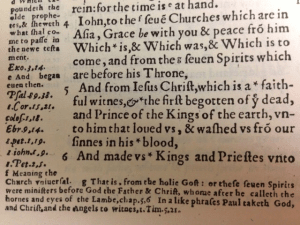

In the fourteen lines of the poem, Shakespeare has shown us a mind working through the process of understanding, really understanding, the meaning of a biblical passage that he must have read, or heard read, on many occasions. The Geneva Bible (1560) was the main translation in use in the English church before the King James translation (1611) and in it we read: ‘Lay not up treasures for your selves upon the earth, where the moth and canker corrupt, and where thieves dig through and steal. But lay up treasures for your selves in heaven, where neither the moth nor canker corrupts, and where thieves neither dig through, nor steal. For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also’ (Matthew 6:19-21).

Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Amazon.co.uk: Shakespeare, William: 9780141396224: Books

PAPERBACK £5.03 (at time of writing)

KINDLE £0.99 (at time of writing)