‘The Sick Rose’ by William Blake (1757-1827)

O Rose thou art sick. The invisible worm, That flies in the night In the howling storm: Has found out thy bed Of crimson joy: And his dark secret love Does thy life destroy.

Considering the Poem

A rose, a worm, a night, a storm, a bed – a life destroyed: with these ideas, William Blake makes a quietly and insidiously disturbing poem that, once read and lodged in the mind, never seems to leave. How does this strange verbal magic work in us? What has William Blake done?

The poem is made from very simple words – only one of them is more than two syllables – and they are drawn from the common vocabulary of a speaker of English. The verse form is humble and unremarkable: very short lines of often (but not always) five syllables, this minor variation causing an uneasy rhythm; the plain rhyme scheme could be found in many a nursery rhyme. The whole work is comprised of two tiny verses and is made from thirty-four words. Nothing in the vocabulary or general form of the verse can account for the poem’s fierce power.

To understand that, we have to understand something about the characteristic way that Blake’s mind works here and in all of his poetry: he is an associative rather than a reasoning, logical thinker. He doesn’t put forward an argument here; he tells a brief story using a protagonist, the rose, and an antagonist, the worm. If stated like this, though, the poem could be a child’s verse.

He does more by enriching the poem with dark associations, symbols and signs. The rose and the worm are each embellished with a cluster of baleful associations. He is thinking both intuitively and imaginatively, drawing us into his thought-world, and stimulating our own ability to think in a dreamlike and intuitive way.

Every word we use has a dictionary meaning that we can look up but the dictionary meaning, the denotational meaning of the word, isn’t what really matters here. The words we use also have a set of associations, or connotations, and these are what Blake sets to work in our minds, as they have worked in his. The connotations of words are the special material of poetry, of course. (In more objective and scientific writing, the aim is to avoid bringing them to mind and thus to keep the spontaneous pathways they open in thought to a minimum.) Blake typically creates a symbolic world in the poem – a world that depends on our grasp of the associative meanings of the words and images he uses.

The poem begins, in formal poetic style, with an address to the rose (1). It appears, however, not to be a particular rose. It stands for all roses seen here, as often in literature, as symbols of perfect worldly beauty. The first two words do not prepare us for the shock of the three words following. The story has begun in a trice: the flower is sick. It is under attack.

When Shakespeare in his Sonnet 146 refers to ‘worms’ (see last week’s article), he uses the word as a symbol that brings associations of putrefaction, death and sin into his sonnet. The associations of this symbol are widespread in Christian literature and usually, as in Shakespeare’s sonnet, are signs that point at our mortality. The Old English form of the word, ‘wyrm’, was used to refer to snakes, serpents – even dragons, on occasion. Associations can cling to a word for a very long time. For Christian readers, the word ‘worm’ may still when Blake was writing have awoken associations of the despoiling done by Satan, incarnated as a serpent, in the Garden of Eden. In Blake’s poem, the setting is also a garden that, like Eden, is ruined by a malicious defiling of innocence.

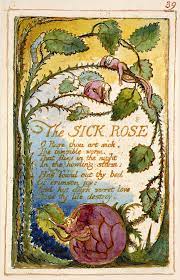

Blake’s illustrated engraving of the poem (see above) shows the worm in the form of a caterpillar, a creature commonly used in literature and everyday language to signal the despoiling of generative growth. Perhaps he has in his mind, too, the larvae of a nocturnal moth.

The worm, simple as it may be in actual life, is a complex tangle of connotations and symbolic qualities in literature, perhaps especially in this poem. Blake, though, makes it quite clear that we are not to conceive of It as a material inhabitant of the physical world. It is ‘invisible’ (2), an immaterial force which, as a vector of spiritual and moral infection, is carrying out an assault on the rose. It ‘flies’ (3) like a disembodied spirit. When we are told that the worm flies in the ‘night’ and in a ‘howling storm’ (4), we know the rose is facing attack from something dreadful, something evil, and something that is travelling in an ominously black and chaotic storm through the noise of ‘howling’, the anguished sound that hell makes. All these associations of danger and disorder cling to the worm, making it a symbol within which many ideas of destruction and decay congregate.

The assault becomes, in the second verse, a violation. The signal for this sinister change is the word ‘bed’ (5). The rose is, of course, in a bed of earth (as Blake’s illustrated poem shows). We also associate the word with our own bed, the most private and personal part of our house, the place in which we trust to our safety even in the vulnerable unconsciousness of sleep and dreaming. The horror is amplified by the carnal and erotic associations of much of the vocabulary in the second verse – the blood-red, ‘crimson joy’ (6), the ‘dark, secret love’ and, of course, the intrusion into the bed itself. The worm has found its way into the rose’s being and ‘found out’ (5), or discovered, its deepest and most private place, insidiously and silently destroying the innocent, joyful life of the beautiful flower from its centre, outwards. The poem is from Songs of Innocence and Experience (1789). It’s easy to see that the sick rose belongs to the dark, fallen world of experience and not to the free, joyful world of the innocence poems.

Blake has found a way to represent the process of evil working in our lives on earth: a way that is not rational or didactic but symbolic and associative. The Sick Rose is a tiny, narrative allegory that works in our own imaginations like a dream, or nightmare, showing the way in which sin and evil penetrate even the most private recesses of our mortal life. Because it concentrates on increasing our awareness of evil, there is little or no hope in the poem.

We need, however, to look at the whole of Blake’s page, both words and illustration. At the bottom of the page, we see the rose, now fallen to the ground, a dying bud. Like Blake’s symbols, his illustrations are often ambiguous. The image might be intended to depict the violation of the rose, emphasizing the dark vision of the poem. We can, though, see it another way. The spirit of the rose, imagined as a young and vigorous female, might be escaping from the sick flower-bud. She seems to have the spread-armed pose that Blake uses to depict exhilaration, energy and joy (as in the illustration, Glad Day [1794]). We also see the worm emerging,, presumably to carry on its endless work of destruction. The rose itself is left to decline and die. Perhaps, at the foot of the illustrated page, in the female figure, Blake has made an image of an irrepressible spirit of joyful energy escaping to live again, at least temporarily, in our fallen world?

PAPERBACK £4.99 (at time of writing)

William Blake: Selected Poems eBook : Blake, William: Amazon.co.uk: Kindle Store

KINDLE £8.60 (at time of writing)