‘Hymn to God, my God, in my Sickness’ by John Donne (1571-1631)

Since I am coming to that holy room,

Where, with thy choir of saints for evermore,

I shall be made thy music; as I come

I tune the instrument here at the door,

And what I must do then, think here before. 5

Whilst my physicians by their love are grown

Cosmographers, and I their map, who lie

Flat on this bed, that by them may be shown

That this is my south-west discovery,

Per fretum febris, by these straits to die, 10

I joy, that in these straits I see my west;

For, though their currents yield return to none,

What shall my west hurt me? As west and east

In all flat maps (and I am one) are one,

So death doth touch the resurrection. 15

Is the Pacific Sea my home? Or are

The eastern riches? Is Jerusalem?

Anyan, and Magellan, and Gibraltar,

All straits, and none but straits, are ways to them,

Whether where Japhet dwelt, or Cham, or Shem. 20

We think that Paradise and Calvary,

Christ's cross, and Adam's tree, stood in one place;

Look, Lord, and find both Adams met in me;

As the first Adam's sweat surrounds my face,

May the last Adam's blood my soul embrace. 25

So, in his purple wrapp'd, receive me, Lord;

By these his thorns, give me his other crown;

And as to others' souls I preach'd thy word,

Be this my text, my sermon to mine own:

"Therefore that he may raise, the Lord throws down." 30

NOTES

(i) ‘Per fretum febris’ (10): through the straits of a fever; in effect to die while journeying through a dangerous fever.

(ii) ‘strait’ (10): a narrow, often dangerous, passage of water linking two different seas; generally, a difficulty.

(iii) ‘Anyan, and Magellan, and Gibraltar’ (18): all straits; the first is usually now ‘Anian’ and refers to a strait wrongly supposed to exist in Donne’s time.

(iv) ‘Japhet’, ‘Cham’, and ‘Shem’: the three sons of Noah, each of whom established rule over a part of the world - Japhet (Europe), Cham (Africa), Shem (Asia)- after the flood.

Considering the Poem

Really, it’s impossible to avoid. Whenever people write something – even a poem as intensely personal as this one – they write as much about the culture and society they live in as they do about themselves. That’s one reason why literature is interesting: it helps us to understand our history, how differently people thought in the past and how the events of history affected people’s hearts and minds.

John Donne lived in a period that’s sometimes called the age of discovery. The most obvious kind of discovery was the outgoing exploration of the earth, its seas, its lands, its geography, its peoples. There were other forms of discovery going on too: medical discovery, for example, that looked not to the great world outside but inwardly to our bodies. Ancient Greek and Roman medical texts were stimulating enquiry and, during the 17th century, advances based on scientific methods (mixed with older ways of thinking) were enriching western medicine. Harvey discovered that blood circulated in our bodies, for example, in 1628 just three years before Donne’s death.

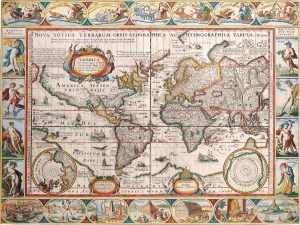

It is wonderful that the idea and image of a world map that’s so important to the poem brings to mind not only the exploration of the external world, (which depended upon cartography, of course) but also, through the use of the word ‘map’ as a metaphor (7, 15) for the doctors’ exploration of Donne’s supine body.

Donne is flat on his bed and the physicians scrutinise and read him just as they would a map (7). In the first verse of the poem we learned that Donne is at death’s door and in the difficult straits of a fever (10). He hopes to make a good death and to ready himself to cross a threshold into the ‘holy room’ where he hopes to join the choir of saints that he will find there. So, while the doctors carry out a physical inspection, Donne is carrying out a self-examination of his soul, a spiritual journey of exploration, which is conducted in the terms of the map image. The points of the compass and the geographical features he mentions all explain something to us (and to Donne himself) about his readiness for death and his likely fate.

The south-west compass point (9) that Donne fears may mark the way to his death is ambiguous. On the one hand, it was possible to reach the riches of the eastern lands by going in this direction, but Donne connects it with a passage through fever and danger. The symbolism of compass points in Christianity is complex and fluid. For Christians, though, the hopeful point is the east, the point at which the sun rises and the point from which Jesus will initiate the final judgement when souls will rise in glory. Thus, Christian graves face east and the most sacred part of a church, the sanctuary containing the altar, is at the church’s eastern end. The south, in this poem, because the image is of the spread paper map with the south at the bottom, has negative associations of descent.

Donne’s process of self-discovery, however, has further to go. His style as a poet often involves chasing down the paradoxes and contradictions of an argument to a tight conclusion. This is what he does here in the process of the argument he is having with himself about his likely destiny. At first, it seems curious that he can insist that ‘west and east/In all flat maps (and I am one) are one’ (13-14). When you imagine a paper map placed before you, however, it’s easy to see that this conceit, or elaborate idea, is really quite simple: the farthest point to the right (or east) of the map is closer than any other part of the real world to the farthest point at the left (or west) of the map. The farthest points of a flat map are, in reality, the closest. If you rolled the map into a tube shape, the two opposites join. From this map image, Donne is able to convince himself (and perhaps us) that all is well. The west of death ‘doth touch’ the east of new life and resurrection (15).

As he brings the idea of exploration and return towards its final stages in the poem, he hopes that the ‘home’ (16) he will return to after death will be a welcoming kingdom (16-17) of peace and spiritual fulfilment, maybe the New Jerusalem itself. The sea-going explorers of his era, by one strait or by another, could reach anywhere on the earth or, as the poem puts it, any of the three earthly kingdoms established after the flood by the sons of Noah, Japhet, Cham or Shem (20). The poet will get to his desired destination too, and he’ll do so by God’s design.

The two final verses carry forward the paradoxical idea of the identity of opposites. But now we leave the east/west map paradox behind. The opposition now in question is between ‘Christ’s Cross and Adam’s tree’ (22). Christ redeemed us from the originating sin of Adam so, the reasoning goes, the Garden of Eden and Calvary, in a spiritual sense, stood in one place (22). We have the pain or work and the sweat of Adam on our bodies; but the blood of Christ, the new or ‘last’ (25) Adam, releases us from error so that ‘purple wrapp’d’ (26) in the royal blood of Christ, Donne maybe received into heaven.

The poem began with Donne’s awareness that he needed to ‘tune’ (4) himself in readiness for the next life and what it may bring. The poem itself is the process of tuning, of joining together opposites that seem, at first sight irreconcilable, so that, in the invocation to the Lord in the final verse, he can hope that the final paradox of all can be resolved and that, just as the priest Donne had preached so often to others, what ‘the Lord throws down’ he can raise (30) to eternal life.

Selected Poems: Donne (Penguin Classics): Amazon.co.uk: Donne, John, Bell, Ilona: 9780140424409: Books Paperback £7.85 or KIndle £2.99