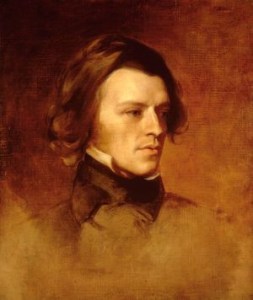

‘In Memoriam: 38′ by Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

The time draws near the birth of Christ:

The moon is hid; the night is still;

The Christmas bells from hill to hill

Answer each other in the mist. 4

Four voices of four hamlets round,

From far and near, on mead and moor,

Swell out and fail, as if a door

Were shut between me and the sound: 8

Each voice four changes on the wind,

That now dilate, and now decrease,

Peace and goodwill, goodwill and peace,

Peace and goodwill,to all mankind. 12

This year I slept and woke with pain,

I almost wish'd no more to wake,

And that my hold on life would break

Before I heard those bells again: 16

But they my troubled spirit rule,

For they controll'd me when a boy;

They bring me sorrow touch'd with joy,

The merry merry bells of Yule. 20

Considering the Poem

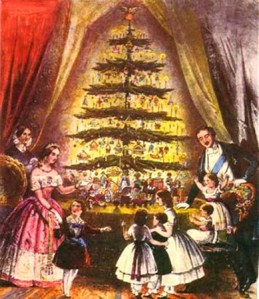

Christmas is a time of general rejoicing and, sometimes, a time of personal, singular sorrow.

The lyric is one of the 131 poems that compose Tennyson’s ‘In Memoriam’ sequence, published in 1850. The series of elegiac poems was Tennyson’s response to the untimely death of his friend, Arthur Hallam, at the age of twenty-two and his attempt to understand, not just Hallam’s death, but the full implications of his death: in fact, the sequence of individual poems is a sustained reflection on whether our lives can have any meaning – not just an incidental or provisional meaning but an essential meaning – when they include random and apparently absurd events like Hallam’s death.

This poem, written just before the first Christmas following his friend’s death in 1833, creates a web of associations that has, at its centre, a persistent feeling of Tennyson’s sorrowing separation from the general joy, a separation that never, however, becomes complete despair. Joy at the birth of Christ pulls one way; personal mourning pulls another. The poem is, like a cloth tautly stretched on tenterhooks, full of tension.

We realise straight away that the speaker, Tennyson, is alienated from the general joy. With masterly simplicity (and a strange, perfunctory tone of voice) the first lines tell us the situation, place and time but they do more than convey facts. They also create a reflective, inward-looking mood by making us feel the poet’s separation from the season of general joy. He hears the Christmas bells ringing from the local churches in the suspended stillness of the night but they ring from ‘hill to hill’ and ‘answer each other’. They do not include Tennyson.

This alienated, dissociated feeling haunts the poem. So many things seem uncertain and incomplete: the ‘time draws near the birth of Christ’ (1) but the poem’s narrative doesn’t quite reach that point in time; the church bells, swell but ‘fail’ (7); their ringing sound fluctuates in strength and clarity as it is carried on the wind (10); then, Tennyson remembers waking from sleep in ‘pain’ (13) and ‘almost’ (14) wishing for his own death, perhaps to join his friend, Hallam.

In fact, the verse form itself has a swell of hope and despair written in to its structure of rhythm and rhyme. Tennyson invented the verse form he uses here especially for ‘In Memoriam’. It is oddly cyclical, each tetrameter line moves forward steadily in iambic units, especially so in the first three lines of each verse, but each verse, by rhyming the final line with the first, seems to end where it began.

This pattern reaches a climax in this poem in the third verse. The four churches, each ring four bells in communication with one another and with the world, their call and response represented in the repeated four syllables of ‘Peace and goodwill’ (11) and then, inverted, ‘goodwill and peace’ (11). We seem to be trapped in a cyclical pattern of repetition.

As it moves towards its conclusion in the final two verses, Tennyson effects a partial resolution of the poem’s uncertainties, incompletions and tensions. The word ‘But’ (17) that starts the final verse introduces a new mood. The bells that Tennyson had heard all his life and which on Christmas Eve embody the general rejoicing at the birth of Christ, now ‘rule’ his spirit (17). Their message of hope now does include him.

In the final lines, Tennyson moves to a point, perhaps not of joy, but, at least, of ‘sorrow touched with joy’ (19). This element of joy is firmly expressed in both the repetition of the Christmas word ‘merry’ and in the rhythmic energy, strengthened by alliteration, that bursts out in the climactic final line of the poem (20). Tennyson has left behind both estrangement and despair and, even if only temporarily, become a part of the general Christian rejoicing.