‘The Oxen’ by Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease. 4

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then. 8

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel, 12

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so. 16

Considering the Poem

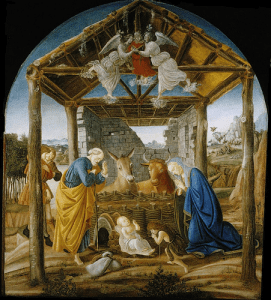

It’s not hard to see why this is a popular Christmas poem. It certainly incorporates many characteristic images and elements of the nativity story: the cattle in the shed, the anticipation of Christmas Eve, the cosiness of friendly people gathered together, the warm fireside conversation and even an old country belief, here the Dorset folk-story that, during the night before Christmas, cattle would kneel in their pen in deference to the imminent birth of Jesus.

Well, cattle do lower themselves by kneeling their front legs so what the folk belief supposes is physically possible. The poem, though, isn’t about whether the oxen do or do not have the bodily ability to do something that resembles kneeling. It is about what it says about life if they do (or don’t) make that gesture on Christmas Eve.

The four verses of the poem are managed in two parts. The first pair of verses, with typical Thomas Hardy economy, set the scene and situation: we are told the exact time; a group of people of various ages warms itself by the fireside and reminisces; the voice of an elder takes the attention of the listeners (and of us, the readers), reminding us all of the old folk tale. What happens next is interesting.

The old man has brought alive in the minds of his listeners the image of the cattle kneeling as he speaks. They are enchanted by a world that could, possibly, include such miracles.

Hardy wants us to understand the effect of the image of the kneeling oxen on the fireside group. The second verse shows us that their imaginations are engaged and that every individual mind ‘pictured’ (5) the oxen, each sensing in imagination the feel of the oxen’s ‘strawy pen’ (6). The hearers are unified, as one, now very much a ‘flock’ (3) with a single, group identity. Not one of them feels any ‘doubt’ (8) because they are suspended in a pure moment of insight and enchantment.

There is then a turn at the start of the third verse. The first two verses had presented a scene from the writer’s youth; the final half of the poem looks back on that remembered scene from the point of old age. He is now the elder in the group of friends but his consciousness is different from both that first elder and from the young listener that he himself had once been.

He now has ‘doubt’. The words he uses as he recalls the elder’s belief in the story of the kneeling oxen are important: ‘fancy’ (9) indicates that the old tale was made by wishful thinking; and ‘weave’ (9) that it involved, like all folk crafts, homely artifice. The old tale of the kneeling oxen now, in ‘these years’ (10), seems to the writer to belong to the believing minds of a previous era.

Hardy was 75 when he wrote this poem. Born in 1840, he had lived through nearly the whole of the Victorian era in England, a period when religious doubt was in the air: geological and evolutionary discoveries had introduced uncertainty into some people’s thinking and, though we in the 21st century may have emerged from those difficulties, they mattered to Hardy and many of his contemporaries.

He is also careful to record the date of the poem’s composition with the title and wants us to take the date into account when we think about what he is trying to communicate to us. By Christmas 1915, the First World War was about fifteen months into its four years of horror and destruction. Many people had thought it would be over by Christmas 1914. Instead it had begun to stick and sink into the muddy despair of an attritional war.

There are quite a few pointedly archaic, rural words and phrases in the poem. We are meant to pick up from phrases like ‘twelve of the clock’ (1) and words like ‘barton’ and ‘coomb’ in the final verse (meaning an area of land next to farm buildings and a valley respectively) the feel of an old, pre-industrial, agricultural England. This is the country to which, in the last two verses, we are looking back. We can now see that the poem is autobiographical. Hardy, the old man, is looking at the past through the lens of his present and is sceptical about the beliefs and assumptions of that long ago time. It is 1915 and the present, with its conflicts and doubts, is nastier and more confused than the remembered simpler and truer time.

The poem, however, doesn’t end in despair but in a sudden rising of hope and a longing for faith. Were someone to invite old Hardy again to come to see the oxen kneel, he would ‘go with him’ hoping to find in ‘the gloom’ (15) a reason to believe not just in the unimportant folk tale of the kneeling cattle but in what that tale assumed: a world with essential meaning and divine purpose in which worship was valid.

Thomas Hardy ‘Selected Poems’ (Penguin)