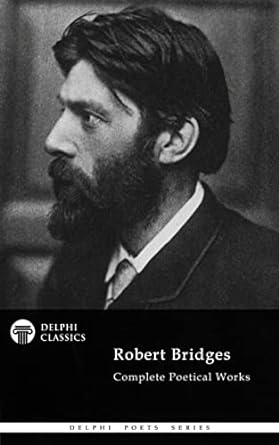

‘Noel: Christmas Eve 1913’ by Robert Bridges (1844-1930)

A frosty Christmas Eve

when the stars were shining

Fared I forth alone

where westward falls the hill,

And from many a village

in the water'd valley

Distant music reach'd me

peals of bells aringing:

The constellated sounds

ran sprinkling on earth's floor 10

As the dark vault above

with stars was spangled o'er.

Then sped my thoughts to keep

that first Christmas of all

When the shepherds watching

by their folds ere the dawn

Heard music in the fields

and marveling could not tell

Whether it were angels

or the bright stars singing. 20

Now blessed be the tow'rs

that crown England so fair

That stand up strong in prayer

unto God for our souls

Blessed be their founders

(said I) an' our country folk

Who are ringing for Christ

in the belfries to-night

With arms lifted to clutch

the rattling ropes that race

Into the dark above

and the mad romping din. 32

But to me heard afar

it was starry music

Angels' song, comforting

as the comfort of Christ

When he spake tenderly

to his sorrowful flock:

The old words came to me

by the riches of time

Mellow'd and transfigured

as I stood on the hill

Heark'ning in the aspect

of th' eternal silence. 44

Considering the Poem

A Poet Laureate has to do two things: he or she, firstly, has to celebrate the culture and history of England and, secondly, the poet has to achieve that by writing interesting but comprehensible poems that communicate smoothly to as many people as possible. Robert Bridges was Poet Laureate from 1913 to 1930. He was certainly one of the most notable holders of this odd and ancient post; he was successful because his poetry fulfilled the two basic requirements of the job perfectly well. This was his first poem as Poet Laureate. How did he fulfil the requirements for celebration and comprehensibility here?

Bridges makes the poem as understandable as possible in several ways. The poem’s structure is straightforward: the first part sets the scene (including introducing the poet as a wanderer through, and observer of, the English countryside and its villages – a typical poetic point of view at the time); the following sections, each with its own verse paragraph (‘Now …’, ‘But …’), explore the nativity in the distant past, then the contemporary rural scene as, climbing a hill, he looks down upon the church towers of the villages spread below him as he ascends; then, finally, the last paragraph relates the two spots in time, the nativity itself and Christmas 1913. This is as clear and, really, as conventional as it could be.

At a more detailed structural level, also, the poem is clear. The pairs of lines each share a common rhythm of sense, the second, indented line, in each case completing or answering the first line in each pair rather like the ‘call and response’ style in music.

The vocabulary is generally fairly ordinary and, for good measure, Bridges sprinkles plenty of old-fashioned, familiar poetic terms through the text – ‘dark vault’, ‘spangled o’er’, ’spake’ and so on. These archaisms are rather comforting for his readers, of course; there’s no need to panic; we know we’re in good hands and aren’t going to be too disturbed by anything completely incomprehensible.

But the poem has an unobtrusive subtlety that makes it interesting – a subtlety hovering just below the surface of the writing all the way through. In part, it comes from what Bridges does with the strange concentration on sound through the poem: he records the angels, or stars, singing at the nativity; the bells of the village churches unfurling across the fields; the ‘starry music’ he hears in the final verse and which assimilates his present, through the churches’ bells, with the bright carolling of the nativity so long ago. What he hears is what was heard at Christ’s birth.

Bridges doesn’t just use the aural imagery for plain, descriptive purposes. Strangely and dreamingly, the poem’s sounds interact across the ages, and even inhabit or melt into other phenomena, for instance in the ‘constellated sounds’ of the first verse – the phrase suggesting that the sounds have solidified into stars – and, again, in the way the stars change into the reflections in the streams, ‘sprinkling on earth’s floor’ (10).

The figures that people the poem, too, connect points in the past with the poet’s England: the simple, poor shepherds and their flock at the nativity of Christ (15) exist still as the worshipful ‘country folk’ (26) and the image of Jesus speaking ‘tenderly to his sorrowful flock’ (38) connects the nativity shepherds with the biblical presentation of Jesus as the shepherd. These creative connections between the people, sounds, sights and events at the time of Christ and 20th century England construct a text full of delicate and implicit correspondences between past and present.

Unusual, too, are darker moments in the poem, particularly, perhaps, the image of the bell-ringers’ twisted ropes, their apparent loss of physical control, and the discordant din their efforts produce (30-32). The poem, also, ends in a suspended moment of unworldly nothingness as the sound-world of the poem quietens, leaving the observer poet ‘heark’ning’ and alone in an ‘eternal silence’ (43-44).

So the poem is quirky, interesting as a text, yet comprehensible.. It does, also, as Bridges’ national role requires, offer a celebration of an English culture that, the poet indicates, is rooted in the meaning of Christ’s birth and that has been preserved, enriched and communicated to us through the churches of these typical villages and the continuity they represent.

Robert Bridges has managed here to do exactly what the Poet Laureate is supposed to do.