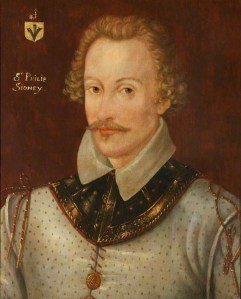

‘Leave me, O Love’ by Philip Sidney (1554-1586)

Leave me, O Love, which reaches but to dust;

And thou, my mind, aspire to higher things;

Grow rich in that which never taketh rust;

Whatever fades but fading pleasure brings. 4

Draw in thy beams, and humble all they might

To that sweet yoke where lasting freedoms be;

Which breaks the clouds and opens forth the light,

That doth both shine and give us sight to see. 8

O take fast hold; let that light be thy guide

In this small course which birth draws out to death,

And think how evil becometh him to slide,

Who seeketh heaven, and comes of heavenly breath.12

Then farewell, world; thy uttermost I see;

Eternal Love, maintain thy life in me.

Considering the Poem

The speaker here seems to be the poet himself or perhaps a persona adopted by the poet that acts as a voice for his personal feelings and hopes. For the first four words, we don’t really know who, or what, is being addressed but we might guess, since we’re reading a sonnet – a form that’s conventionally used for love poetry – that the words ‘O Love’ are addressed to a particular, known person, a lover or a mistress, that the speaker asks to leave him now that the amorous meeting between them is over.

Sidney knows, of course, that we have this kind of expectation as soon as we see that we are reading a sonnet. He keeps us playfully in suspense for a moment and then begins to disobey our expectations about who or what is being addressed. The last five words of the first line tell us that the love of which he talks is a love that passes away into nothing so we realise that, in fact, he is addressing (indeed, dismissing) not any single, particular lover but a general idea, or personification, of love in its sexual and romantic form. This is the form of love that must end, everywhere and always, in dust. Then, in the second line, the poet turns inward and aims his comments at his own ‘mind’, the immaterial part of himself that may, he hopes, help him to ‘aspire to higher things’ (2). The higher thing he is concerned with in the poem is the love of God.

The fourteen lines of the sonnet are organised in the English form with four sets of lines: three sets of four lines (or, quatrains, to use the literary term) taking us to the twelfth line. Then, the sonnet rounds off with two rhyming lines, a couplet (13-14). The tightness of the structure is emphasised here by the fact that at the end of each quatrain (4, 8, 12), the sense is halted by a full stop. Sidney hopes to make reading easier for us not just be basing the poem on the opposition between worldly and divine love but also by this orderly management of the sense in which syntax and the versification of quatrains (and the final couplet) begin and end together. We know that each section will take the sense of the poem forward in manageable steps. We know who is speaking, to whom, what about – earthly ‘Love’ and a ‘higher’, spiritual love – and, because we know how sonnets are usually organised, we can prepare ourselves to follow through the sense of the poem step by step, section by section.

The first quatrain neatly explains the problem. Philip Sidney knows he has come to a point in his life at which he must leave behind appetites, desires and emotions – attachments, really – and try to use his mind, to reach up to grasp at a golden, spiritual world, a world in which nothing fades away, turns to dust, or rusts like an inferior metal (3-4). He knows that all worldly and carnal pleasures ‘fade’ and therefore can only give a temporary fulfilment.

So, the poem relies on an opposition between two kinds of love: the earthly and the spiritual. The key quality of earthly love is established in the first four lines and so, in outline, is the contrast between the two loves. Sidney’s aim in the second quatrain is to make concrete for a reader the qualities of the spiritual love for which the poet longs and to which he aspires. This is achieved through a concentrated sequence of images that indicate light, joy, freedom, sweetness and true, clear vision. By the time we have read the second quatrain, we understand what Philip Sidney means by the ‘higher things’ he seeks.

Both the person being addressed and the tone of the verse change at the start of the third quatrain: the word ‘thy’ (9) in the exhortation ‘O take fast hold; let that light be thy guide’, (9) is not addressed to the personified figure of carnal love (1) but encompasses both the poet’s mind and us, the readers. Our relationship with the poet changes; it is now personal and direct. He has suddenly turned his face directly to us in an effort of persuasion, imploring us to accompany him as he struggles to keep his mind fixed on the celestial, guiding light that is all we have on our short journey (or ‘course’) through a life in which it is all too easy for evil to bring into existence (‘becometh’, 11) weakness and backsliding.

The final couplet rounds off the process of understanding that the poem has dramatized in one man’s address to worldly love, to his own mind and to us. He has seen and understood the ‘uttermost’ (13) limits of worldly love (which sonnets, of course, are usually devoted to celebrating) so the final seven words of the poem make a quiet denouement – a prayer that a new ‘Eternal Love’ (14) will live in him like a kind of infilling grace, replacing the fragile earthly love with which the poem began.

Astrophel and Stella by Sir Philip Sidney (CreateSpace Independent Publishing)