‘The Coronet’ by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

When for the thorns with which I long, too long,

With many a piercing wound,

My Saviour’s head have crowned,

I seek with garlands to redress that wrong:

Through every garden, every mead, 5

I gather flowers (my fruits are only flowers),

Dismantling all the fragrant towers

That once adorned my shepherdess’s head.

And now when I have summed up all my store,

Thinking (so I myself deceive) 10

So rich a chaplet thence to weave

As never yet the King of Glory wore:

Alas, I find the serpent old

That, twining in his speckled breast,

About the flowers disguised does fold, 15

With wreaths of fame and interest.

Ah, foolish man, that wouldst debase with them,

And mortal glory, Heaven’s diadem!

But thou who only could’st the serpent tame,

Either his slippery knots at once untie; 20

And disentangle all his winding snare;

Or shatter too with him my curious frame,

And let these wither, so that he may die,

Though set with skill and chosen out with care:

That they, while Thou on both their spoils dost tread,

May crown thy feet, that could not crown thy head.

Considering the Poem

We do seem to think of upwards as the way to goodness and downwards as a way to badness of one kind or another, placing ourselves at a middle point in the scale, capable of both falling and rising.

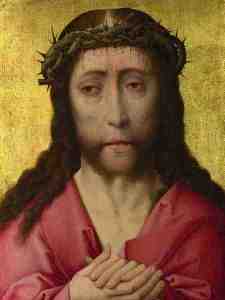

This common opposition is certainly one of the organising devices that Marvell uses to make a framework for this poem, which starts at the top of a body, Christ’s head crowned with thorns, and moves down (appropriately, at the foot of the verse itself) to end with Christ’s feet as they crush the spoils of pride and self-concern that have debased our lives and accomplishments here below.

The other duality that acts as an organising device in the poem is the opposition between, on the one hand, a garden of innocence and, on the other, a garden that incorporates evil in the form of the ‘serpent’ (13). These two gardens are represetations of Eden before and after the Fall but Eden is presented not in biblical terms but in the manner, commonly used and explored in Renaissance poetry, of the pastoral – a type, or genre, that Elizabethan poets of the English Renaissance like Marvell inherited from the literature of classical Greece and Rome. The inhabitants of the pastoral garden are, as here, idealised shepherds and shepherdesses leading a life of love and leisured simplicity.

The voice in the first part of the poem does at moments seem to be that of a pastoral shepherd but we very quickly become aware that he is not a standard genre character: although he talks of his worldly love, his Shepherdess (8), and the high, floral garlands he makes for dressing her hair (7), his true interest (and anxiety) is the injury done to his ‘Saviour’s head’ (3) by the crown of thorns. Pastoral shepherds, living fictional lives inside pastoral poems, are not generally Christians but this one is.

He is tortured by the sufferings of Christ, endured on his behalf, and tries to make amends by seeking flowers through the gardens and meads of his idealised literary landscape to make a garland for the injured head of Christ (4-6). The generic pastoral shepherd is always in love and seeking worldly pleasure and satisfactions but the figure in Marvell’s poem deviates from the genre norm – again in his Christianity: he wishes to dismantle (7) the floral garland he’s made for his lover to make a perfect garland for the Christ that has been crowned with thorns (6-12). The making of the garland, or ‘chaplet’ (11) will be an act of contrition and repentance.

It’s not just the hair arrangements that are coming apart and being remade as we read the poem. Marvell is dismantling the pastoral world and replacing it with a more complicated, difficult one – an world-garden which includes guilt, repentance and the need to make a symbolic action – finding a new crown for Christ – that expresses that guilt and a desire for forgiveness.

In structural terms, the most important word in the poem is the exclamation ‘Alas’ (13). It is exactly at the poem’s mid-point and, like a literary hinge, marks the final point in the move away from the (now dismantled) image of the pastoral world of classical literature to the image of the Eden garden on the point of the Fall. The crawling, horizontal serpent, the passage through which evil will find its way into human life, weaves itself into the fertile luxuriance and beauty of the tangled mass of flowers (14-16). There could hardly be a better image than this of the apparently indivisible mixture of good and evil, of beauty and ugliness, of fragility and power, of suffering and love, which is the heart of a Christian conception of the world. The serpent has woven ‘wreaths of fame and interest’ (16) into the floral world and these characteristics of self-interest, partiality and the desire for fame debase (17-18) us here in the poem as they did originally in the Genesis story.

Marvell moves to the end of the poem by addressing two imagined hearers: one is addressed as ‘thou’ (19) and the other, capitalised, as ‘Thou’ (25). The capitalised ‘Thou’ has to refer to Christ. The other ‘thou’, following the rule that, if a pronoun is being used, it must refer back to the most recent noun which, in this case, is ‘foolish Man’ (17). Taking it like this, Marvel is telling us that we have responsibility for our fallen nature: we could have controlled its effects by disentangling the slippery knots of the serpent’s evil work in our lives (19-20). We could also have curtailed our vain desire for ‘fame and interest’ (16).

The poet earlier (10-12) made a ‘curious frame’ (22) of flowers that he hoped could express repentance for the injury done to Christ by the crown of thorns. The poem itself, ironically, is also a ‘curious frame’, a highly-worked and elaborate human artefact, and so, too, is probably just another act of pride. So, in the end, Marvell tells us that Christ is the only ‘Thou’ that has the power to kill the serpent (23) and the spoils (25) of self-interest and the desire for fame that the serpent has created in us (25).

The final eccentric image of crowning Christ’s feet shows us Marvell up-ending and completing the variations of the vertical, up to down, higher and lower, head to foot idea that has done so much to hold the poem together from its first words, through the rejection of amorous sexual love represented by the dismantling of the sheperdess’s garland, through the idea of the re-crowning of Christ, through the contrastingly low and horizontal movements of the serpent and ending here, in the strange final image which brings the spatial ideas to an eccentric culmination and, because Christ’s feet touch the earth, suggests the reconciliation of God and man, through Christ.

Andrew Marvell ‘The Complete Poems’ (Penguin)