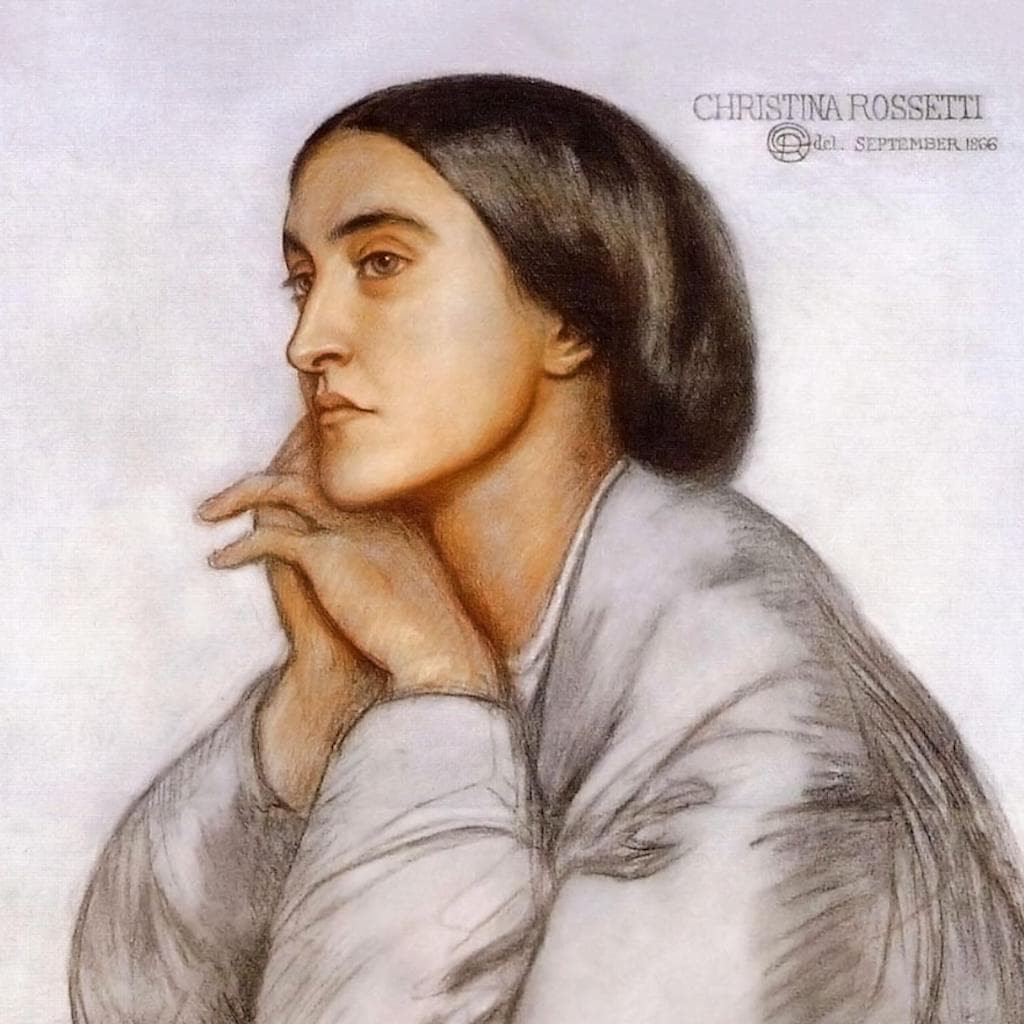

‘Mary Magdalene and the Other Mary: A Song for all Maries’ by Christina Rossetti (1830-1894)

Our Master lies asleep and is at rest.

His heart has ceased to bleed, His eyes to weep:

The sun ashamed has dropt down in the west:

Our Master lies asleep.

Now we are they who weep, and trembling keep

Vigil, with wrung heart in a sighing breast,

While slow time creeps, and slow the shadows creep.

Renew thy youth, as eagle from the nest;

O Master, who has sown, arise to reap -

No cock-crow yet, no flush on eastern crest,

Our Master lies asleep.

Considering the Poem

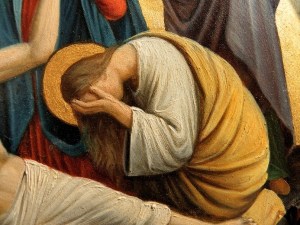

Nothing happens in this little poem. There is no narrative element, at least in terms of a development of action or events. The synoptic gospels agree that Mary Magdalene was present at the burial of Jesus and saw his body (Matthew 27:57-61; Mark 15:42-47; Luke 23:50-56). Christina Rossetti is interested solely in the state of mind of Mary Magdalene, the voice of the poem, and in representing her thoughts and feelings during the twilight bleakness of Easter Saturday’s evening (3), after the crucifixion, which she had also witnessed, and before the resurrection. As all Christians do each year at this point in the Christian calendar, Mary waits, suspended between hope and despair. By listening to her voice, we can understand and so intensify our own insight into this short and intense period of time. The poem’s purpose is, in other words, devotional.

The rich allusiveness of Rossetti’s poem makes sure that it is not only able to tell the truth about the emotions involved at that dark time but is also able to put that temporary truth into the context of the permanent truth created by what will happen on Easter Sunday which, for Mary, as she speaks, is yet to come. Part of that allusiveness comes from the ambiguities of the poem’s language, especially at its start: Jesus’ heart’s blood and his eyes’ tears no longer flow (2) because his earthly body has died but the words also remind us that his blood and suffering have purchased redemption and the hope of eternal life for believers. These ambiguities capture the complexity of the temporary and permanent truths that Rossetti presents.

Mary speaks for the other women – including the other Mary – who the gospels indicate accompanied her at the tomb. The statement ‘Our Master lies asleep’ is made three times in the poem (1, 4, 11): to open the poem assertively, to compose the final, short line of the first verse (half the length of the other lines by syllable count, and so, with its listless cadence, sad in feeling), and to end the poem. The other women are a bridge leading from Mary Magdalene’s personal experience to the experience of all Christians then and since, sharing the agony that immediately precedes Easter Sunday. So, during the second verse, the sorrow passes from Jesus to the witnesses: they seem to inherit it from the sleeping ‘Master’ (4) and to bear it in weeping, trembling, sighing and in their ‘wrung’ hearts (5-6) while time and twilight dull down in a lifeless ‘creep’.

The sense of suspension is intensified by Rossetti’s verse structure. There are many strongly punctuated stops at the end of verse lines in the first two verses. This gives the verse a kind of halted, hanging feel, matching the halted life that Mary describes. Then, at the end of the second verse, the poem slows further. This sensation of slowing to nothing comes from the repetition of the words ‘creeps’ and ‘slow’ (7) but the minimal version of movement suggested by these words is also manifested in the ponderous rhythm of that line: it has the same number of syllables as all the other longer lines but it has six rather than five main stresses and these accents are rather uncomfortably bunched in the phrases ‘slow time creeps’ and ‘slow the shadows creep’, inhibiting the reading when you try to say the line aloud. The movement of the verse embodies the lifelessness that is its subject.

The poem cannot end purely in that mood because there is the other, permanent truth to tell or at least to indicate – not just the temporary one about sleep, about waiting in despair, about time suspended and twilight desolation, but the other truth, the permanent one, about celebration and renewal.

Mary turns to address Jesus directly in the third verse, exhorting him to ‘arise’ (9). She can hope and trust but she cannot, at that moment, know. The reader, however, does know that the awakening will happen, that the flush of brightness in the east (10) will indeed replace the setting sun in the west (3). We know more than Mary who is left waiting at the end of the poem. We know the permanent truth and are reminded of the longer view by a set of allusions that may be strongest in the vocabulary used at the end of the poem but have run all the way through the text: from ‘bleed’ [2], to ‘sown’ [8], to ‘arise’ [8], to ‘reap’ [8], and to ‘cock crow’ [10], all reminding us by allusion of the whole Gospel story and the full meaning of Jesus’ life.

Christina Rossetti: Selected Poems (Penguin)