‘Good Friday, 1613, Riding Westwards’ by John Donne (1571-1631)

Let man’s Soul be a Spheare, and then in this,

The intelligence that moves, devotion is,

And as the other Spheares, by being growne

Subject to foreign motion, lose their owne, 4

And being by others hurried every day,

Scarce in a yeare their natural forme obey:

Pleasure or businesse, so, our Soules admit

For their first mover, and are whirld by it. 8

Hence is’t, that I am carried towards the West

This day, when my Soules forme bends towards the East.

There I should see a Sunne, by rising set,

And by that settling endlesse day beget; 12

But that Christ on this Crosse, did rise and fall,

Sinne had eternally benighted all.

Yet dare I almost be glad, I do not see

That spectacle of too much weight for mee. 16

Who sees Gods face, that is selfe life, must dye;

What a death were it then to see God dye?

It made his owne Lieutenant Nature shrink,

It made his footstool crack, and the Sunne winke. 20

Could I behold those hands which span the Poles,

And tune all spheares at once peirc’d with those holes?

Could I behold that endlesse height which is

Zenith to us, and our Antipodes, 24

Humbled below us? Or that blood which is

The seat of all our Soules, if not his,

Made durt of dust, or that flesh which was worne

By God for his apparel, rag’d and torn? 28

If on these things I dare not looke, durst I

Upon his miserable mother cast mine eye,

Who was Gods partner here, and furnish’d thus

Halfe of that Sacrifice, which ransom’d us? 32

Though these things, as I ride, be from mine eye,

They are present yet unto my memory,

For that looks towards them; and thou look’st towards mee,

O Saviour, as thou hang’st upon the tree; 36

I turne my backe to thee, but to receive

Corrections, till thy mercies bid thee leave.

O thinke mee worth thine anger, punish mee,

Burne off my rusts, and my deformity, 40

Restore thine Image, so much, by thy grace,

That thou may’st know mee, and I’ll turne my face.

Considering the Poem

Who, on a journey, has not realised with a jolt that they’re going the wrong way?

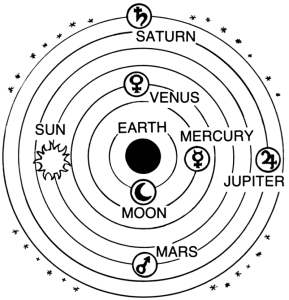

This simple and common experience is the germ of Donne’s famous Easter poem. He begins it with an extended analogy that compares his ‘soul’ with a ‘sphere’ (1-8), one of the circular paths, concentric around the earth, that each planet moved along through the sky according to the Ptolemaic idea of the universe. Knowing it is a difficult figure of speech, Donne courteously asks for our indulgence and patience (1). His choice of analogy, based as it was on a medieval view of the heavens that was already fast becoming archaic, was developed also from the scientific truth that the motion, and so path, of a planet is influenced by its nearby planets. In Donne’s poem, his soul is being drawn out of its true course. In the circumstances, as we’ll see, he’s travelling the wrong way.

The cosmological perspective is combined with an eye-level, cartographic point of view in the poem. Donne is travelling from England to Wales – the home of his ancestors and family. But it is Good Friday so he should not be travelling west, drawn by worldly objectives of “Pleasure or businesse” (7), but facing towards a rising eastern ‘Sunne’, the compass point from which Christ’s second coming is expected and so one symbolic of hope, resurrection and the new Jerusalem (9-12). This direction should be his true course.

As he rides, he voices his thoughts and imaginings as they occur and we read them as if in real time with him. The poet’s exploratory reflection makes the main substance of the poem (13-35) and begins with a musing on the atonement for our sin made by the selfless suffering of Christ on the cross; but this train of thought leads Donne into dark moments. Perhaps he should ‘almost be glad’ (15) that, by facing west, he does not have to see the face of God, the cruelty of the crucifixion (15-16), the disruption in nature that accompanies the crucifixion (19-20), the details of Christ’s suffering, his body ‘rag’d and torn’ (28), and his mother Mary’s misery (30). By not seeing, he might avoid the numinous terror created by those images.

Not looking, though, cannot entail not knowing: the fearful images are lodged in his ‘memory’ (34) whichever way his body is facing and travelling. In his reflection, Donne renews his awareness of the meaning of Christ’s life and death. The strange image of the figure of Christ, whose nail-pierced hands hold fast the poles not just of the earth but of the universe, and ‘tune all spheares’ (21-22) – including the imagined sphere of Donne’s soul – marries the cartographical idea of the poles with the cosmological planetary system, and crystalizes Donne’s renewed insight into Christ’s presence at the very centre of the world and of all life, of all order.

The poem transforms itself from reflection to prayer as it reaches its end (39-42). Donne asks that his soul may be made pure, that his ‘rusts’ and ‘deformities’ (40) may be burned off by the transformative power of Christ’s fierce grace. The idea that his sins need to be ‘burnt off’ by Christ’s action shows here, as often in his writing, that Donne is painfully aware of the fearsome power that will be needed to correct his errant, human soul. Sometimes, often because of unusual figurative ideas like the sphere and soul comparison in this poem, Donne may seem a rather intellectual poet; but his work is driven by extreme, often desperate, personal emotion. This is the case here. The reflections in the poem are organised as a crescendo of personal guilt that reaches a climax in the image of the stare of the dying Christ looking directly and specifically at Donne (35-38).

What Donne has not seen with his back turned to the east and his face turned to the west, he has been forced to confront in his imagination and “memory” (34) so, as his wayward body continues westward, his mind does in fact, and ironically, turn in its proper direction towards the rising sun (and Son) in the east. At the end of the poem Donne has responded to his bodily misdirection with the totality of his inner humanity – his mind, his heart, his imagination and his faith. He achieves correction. Bringing us with him through the process of thought and feeling that is the poem, he has re-orientated himself and turned his soul to face east towards the rising Christ while in body he rides on, westwards, to fulfil worldly aims.

‘Selected Poems’ by John Donne (Penguin)